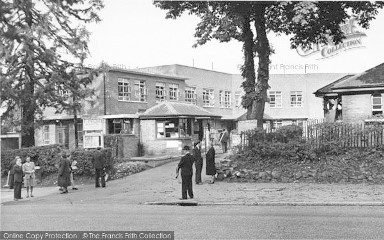

FARNBOROUGH HOSPITAL

This article was written before the old Farnborough Hospital was closed and demolished to make way for what became the Princess Royal University Hospital. The article was written

by John F Hackwood and consists of reminiscences from when he was Surgeon Superintendent during the period 1928 - 1964. It was first published in four parts in the magazine of the Bromley Borough Local History Society during 2003-4, and is reproduced here with their permission.

Part One - The Early Years

Some of the great London teaching hospitals can trace their origins back to the middle ages but the site on which Farnborough Hospital now stands was rough scrubland 120 years ago.| During the depression of the 1840s there were large numbers of desperate poverty stricken people herded in the slums of the towns or wandering around the countryside. The government of the day passed the Poor Law Bill to deal with this problem, not it is feared entirely from philanthropic reasons, but in order to prevent disorder and to reduce the prevalence of disease - in those days outbreaks of cholera, typhoid and smallpox were frequent and tuberculosis was widespread. |

|

Under this new act towns and urban districts were instructed to build workhouses and infirmaries to house and treat the destitute. These workhouses were as a rule as far from the ‘respectable’ areas as was possible. For this reason the Bromley Board of Guardians purchased the site on which the hospital now stands for £200. An old parchment agreement dated 1858 gave the Guardians authority to raise a loan of £8000 to build and equip the new workhouse and infirmary.

The old workhouse buildings were still in existence in 1930. There were tall dark forbidding structures standing on the site of the Surgical block and the Obstetric unit. There were also infirm wards and a babies ward between the Path. Lab. and the administrative block. The oldest surviving part is the main dining hall with its high timbered roof. Outside the mortuary is a deep well, now covered over, which supplied the workhouse with its water.

The actual workhouse was under the autocratic control of a master and matron, always man and wife, and in charge of the infirmary section was a superintendent nurse. Medical supervision was provided by a visiting general practitioner

There were usually about 500 destitute inmates in the workhouse proper with a varying number in the infirm beds. The sick were later housed in the blocks built in 1910 - the one now containing the library and the creche and the other housing the outpatient department. These wards had painted brick walls and rough wooden flooring. The healthy children were housed in the present psychiatric block and were marched off each day to the village school.

In the far comer of the grounds beyond the boiler house was a grim prison-like structure, the Casual Ward. This admitted the wandering tramps and vagrants each evening when they received meagre rations and a sleeping cell in return for a days work in the grounds. Until quite recently could be seen a row of ground floor cells with meshwork in lieu of windows. The casuals had to break stones in the cells until they were small enough to pass through the openings in the meshwork until their allotted work was completed. Records show that the master periodically ordered 30 tons of stone for this purpose.

This was the position when I came to Farnborough in 1928. It transpired subsequently that the Ministry of Health had insisted on the appointment of a whole time resident doctor to supervise the day to day treatment of the sick, particularly as the number of road accidents was increasing. At that time there were no sizeable hospitals except Farnborough between Tunbridge Wells and Lewisham. Furthermore the General Nursing Council had threatened otherwise to withdraw the nurses training school, this being about four yeas after the S.R.N. examinations were instituted

I have often recounted details of the interview with the Board which still remains fresh in my memory after fifty years. All the candidates but two of us withdrew after being shown around the hospital. I myself had very serious doubts about the post. Since, however, it was extremely difficult in those days to move from deputy to chief in the Poor Law service and since there was also a new rent free house in Ninhams Wood being offered I decided to risk it with a view to regarding it as a stepping stone to better things. When asked how the absence of electricity would affect the work, I suggested that this difficulty had been overcome in the past and would no doubt not prove insuperable, inwardly deciding that it was going to cost them in the near future. They asked how I would manage without X-Rays whereon I told them I would just have to become a little more skilful in diagnosis. Subsequently I heard that the Board considered this a very smart and commendable point of view!

Part Two - the Poor Law Board of Guardians

Famborough Hospital in 1928 was good in parts - the wards were

scrupulously clean and the grounds beautifully maintained but during my

first few months it became very apparent that it would be a long and

uphill task to bring it into line with more modern general hospitals.

Having served under three successive authorities - the Board of

Guardians, the KCC and the N.H.S. - I can affirm quite definitely that

the first two years under the Guardians proved to be the toughest

assignment of my career.The local press reported at the time that the Board was most anxious to upgrade the hospital but what was not mentioned was that this was to be carried out with the most stringent and unbelievable economy. I was often warned that every thousand pounds on staff or equipment meant a penny increase on the local rates and on one occasion was even questioned in the full committee as to why it was necessary to purchase a new adenoid curette costing then only 8s 6d.

There were 250 beds with a large proportion of long stay patients and only one lady A.M.O. to assist. Fortunately she was a very good physician and anaesthetist. There was no consultant advice available which proved to be a great drawback when the admissions began to increase since they included all the specialities. The surgery was not abundant at first as most operations in those days were carried out by general practitioners at the local cottage hospitals. There was a small operating theatre heated by a gasfire which, of course, had to be extinguished before the anaesthetic began. The A.M.O. also had to act as pharmacist which was not really difficult as the dispensary consisted of about a dozen large bottles of concentrated mixtures and a few boxes of pills in common use.

There was no path. lab. and all specimens had to be sent by post to Maidstone. For the first year I had no clerical assistance and had to provide my own typewriter for reports and letters to doctors but a typist was finally agreed to at a salary of 30/- a week. There were only four battery-run antiquated telephones for the whole hospital. The Board would not allow any outpatients, anti-natal clinic or casualty department as it was considered that such facilities might encourage patients to seek admission to the already overcrowded wards.

The greatest drawback was the absence of electricity. The wards were lit by gas and portable paraffin lamps - indeed the gas pipes are still embedded in the concrete of the Edward/Mary block. Patients needing X-Ray had to be sent to Bromley Cottage Hospital although occasionally we could call in the Portable X-Ray company. Their accounts, however, were always closely scrutinised and at times criticised by the Board. It was a long and difficult struggle to get them to change from gas to electricity. These deficiencies were counterbalanced by an excellent little training school and extraordinary keen nursing staff. Sisters were paid £75 per annum. The student nurses were paid £25 per annum and were fined for ward breakages. They also had to pay a fine of £10 if they discontinued their training. Ruled over by a real 'Florence Nightingale' the discipline was strict beyond belief. They were forbidden to leave the hospital grounds at any time without permission - the grounds incidentally were escape proof, being completely surrounded by eight foot spiked railings. Instructions issued at the time included "no ink, food or artificial light in bedrooms. Nurses must be in their rooms by 10pm. Lights out by 10.30 pm."

I fought many battles with the Board to have these ridiculous restrictions relaxed but met with considerable resistance from 'Florence Nightingale' and from the ladies on the Board who, I am sure, feared the worst. I had to give all the lectures to both preliminary and final nurses which involved considerable study on my part in some of the less familiar subjects.

In 1929 two events occurred which were very gratifying. Electricity was at last installed throughout the hospital and the Edward/Mary block was completed and put into use (at a total cost of only £26,000.) At the time it was considered to be the last word in ward construction but sadly has had to wait nearly fifty years for upgrading. In spite of the new block, the wards soon became overcrowded. There were always beds in the centre of the wards and sometimes in the corridors since at that time we could not refuse any patients sent in by the District Poor Law medical officers or the relieving officers who dealt with the destitute.

Finally it was agreed as an economical and purely temporary measure to construct thirty wooden cubicles in a U pattern round the present X-Ray and outpatient department. These huts have always been very unpopular with the staff but remained in use for many years.

In 1930 the Boards of Guardians were abolished and the Kent County Council took over the hospitals.

Part Three - An Expanding Hospital

In 1930, we were taken over by the Kent County Council and the prospects immediately became brighter, thanks to the enthusiasm and friendly co-operation of Dr A Elliott, the County Medical Officer, to whom the hospital owes a great debt of gratitude.I immediately submitted outline plans for three new ward blocks and a new nurses' home to deal with the rapidly increasing pressure on the beds. This was largely due to the enormous increase in house building throughout the surrounding area, but also, I like to believe, to a slowly increasing acceptance of Farnborough as a hospital and not an infirmary.

The resident medical staff was increased to six, to my great relief. Mr C Cookson was appointed as deputy superintendent and assistant surgeon.

The first plans to be approved -the three story surgical block and the nurses home -were finally completed and in use for several years before the war. The increase in local housing had also intensified the demand for obstetric and paediatric beds. Plans were again approved for these and the obstetric unit was opened early in the war. The paediatric unit was not occupied until some time later owing to damage to the roof by an oil bomb.

There were no house officers in those days and the Assistant Medical Officers shared medical and surgical wards and also gave anaesthetics. We all shared the long stay wards, and changed around every three months to avoid stagnation, but there was no really intensive geriatric care. The number of operations performed annually had increased greatly since 1928 and the Kent County Council approved plans for a new operating theatre and an X-ray department. It is interesting to note that each of these buildings then cost only £5000 each. The pharmacy and the pathological laboratory were also built at about the same time.

In the early thirties, Mr Hatcher was attached to us as laboratory technician, in liaison with the County Laboratory at Maidstone, and together we set up a mini laboratory in a small room opposite the top of Mary Ward staircase. Later he was for many years the senior technician in the new path. lab.

But I remember him more for his energy and enthusiasm in first suggesting and later acting as secretary and treasurer of the staff social club. His enthusiasm eventually overcame many difficulties, mostly financial. I remember that for a long time the matron would not agree to any membership apart from nursing staff. In the event of a nurse wishing to invite a male friend to any of the functions he first had to be carefully vetted and approved by the matron's office. It was also insisted that when dances were held there must also be a whist drive in an adjoining room for the less agile members of the staff.

The senior ambulance driver, Mr Hone (?), generously provided the band for many years. The dances were held in the dining hall until the new nurses' home was completed and members of the senior nursing staff were always posted at each of the doors throughout the evening. The club later, of course, embraced the whole of the staff and gradually became financially viable. It was very gratifying to Mr Hatcher, the original driving force and myself, when the new social centre was finally opened.

During the late thirties I submitted plans, to the County Medical Officer, for a two hundred bed extension of the main hospital on the land now occupied by the car park and the post graduate centre, together with new theatres, X-ray, casualty, out-patient and reception departments. The main entrance was to be in Crofton Road. These plans were approved in principle by the county council and a sum of £250,000 allocated for the purpose. Had it not been for the war these buildings would now be in use.

Finally an interesting sidelight on the progress of inflation is contained in the County Medical Officer's annual report for 1938 when the weekly cost of each patient in Farnborough was £2 8s 4d (£2.42p) almost exactly one hundredth of the figure forty years later. Do any of our readers know the cost 70 years later?

Part Four - Wartime and the coming of the NHS.

During the spring and summer of 1939, the hospital staff shared the

wishful thinking of the time that the Hitler-Chamberlain pact really did

mean 'peace in our time' but this complacency was rudely shattered when

we were informed that the ground behind the psychiatric block was to be

cleared for the erection of twelve hutted wards. These were completed

and equipped in an amazingly short space of time. Two additional

theatres were provided at the same time, one which is now the ENT.

theatre and another with three tables on the ground floor of the

psychiatric block. Extra beds to bring the total complement to 1200 also

arrived but fortunately were never needed.When war was finally declared in September, it was thought that heavy bombing would start immediately. Coach loads of Guy's medical and nursing staff arrived during the first few weeks and varying accommodation was provided by billeting in the neighbourhood. Bassett's school was appropriated for use as a nurses' home. About forty Guy's medical staff arrived -I remember particularly Messrs. Davies Colley, Grant Massey, Stamm and Gibberd with Doctors Mutch and Payling Wright, many of whom returned to Guy's after a few weeks of inactivity but Mr Davies Colley and Dr Mutch remained with us throughout the war. We had the luxury of house officers for the first time and a mobile surgical team was formed which was very active during the air raids. About 250 Guy's nurses arrived and took charge of half the wards under their own assistant Matron.

Co-ordination of the two separate staffs was not easy. The medical staff quickly settled down largely aided by the 'father figure' of Mr Davies Colley who was a stabilising influence throughout the war. The two separate nursing staffs proved somewhat of a problem for some time as there were two Matrons with rather different views on nursing administration and discipline, but I was greatly assisted by Miss McManus, the Guy's Matron whom I found most charming and helpful throughout.

The hospital suffered less from the Blitz than many others but several incidents stand out during this period. Our first large inflow of casualties occurred in August 1940 when Biggin Hill was severely bombed. The new obstetric block had been completed and occupied a short time previously and I was anxious to perform the first operation in the new Theatre. This proved to be a Caesarean and as the anaesthetic was being induced the air raid warning sounded and very soon afterwards the raid on the airfield began - incidentally one of the noisiest we experienced. While waiting for the suture I glanced out of the Theatre window and saw a big German bomber flying low over the wards and feared the worst for the hospital. It was however out of control and shortly afterwards crashed on Keston Common. The injured pilot and co-pilot were admitted to us and for security reasons were nursed under an armed guard on the top floor of the three storey surgical block. The pilot who spoke perfect English was not what one would describe as a friendly soul, and protested most strongly at being detained in what he regarded as an unfairly exposed position but he made it quite clear that he would be released in a few weeks time when the forces of the Third Reich arrived in England. The co-pilot was a very decent chap with whom I had several chats with the aid of a German dictionary.

A few weeks later an oil bomb was dropped on the newly completed paediatric block which delayed its opening for some time, also a small number of incendiaries only one of which fell on one of the hutted wards and was promptly extinguished with great presence of mind by one of the Guy's students. The most serious incident occurred during a dark and cloudy night in October. Two bombs fell, one just outside the sister's office on Edward ward and one alongside the three-storey block. A smaller one fell on the ward kitchen, where the library is now sited, killing the ward sister. Only two patients were killed in the two damaged blocks but most of the windows were broken and there was naturally considerable chaos. Dr K.O Rawlings, who was then seconded to us from Guy's, did a sterling night's work by collecting up the Home Guard who were stationed nearby and transferring all the 150 patients in Farnborough Hospital down to the hutted wards from where they were transferred to other hospitals next day. The hospital fortunately suffered no further damage but on several occasions in 1944 received a large number of casualties when flying bombs fell on Bromley and Beckenham.

Apart from the ward sister killed during the 1940 raid, the staff lost one of the senior ambulance drivers who disappeared during an Atlantic patrol and the steward's senior clerk was killed with his family when their air raid shelter in the village was hit.

The first few years after the war proved to be an anticlimax and probably one of the dullest periods in the hospital's history. The Guy's medical and nursing staff quite naturally returned to their own hospital as quickly as possible and this necessitated the closure of five wards. Personally I shall always remember with gratitude those members of the staff who remained with us and assisted in our recovery -particularly Messrs. Cookson and Van Meurs with Doctors Rawlings, Gilchrist and Wakeham. In addition the recently appointed senior staff, Mr Rufus Thomas, Dr Leys and Mr Lipscombe were organising their respective apartments as separate units -obstetric, paediatric and ENT.

In view of the forthcoming NHS. it could hardly be expected that the Kent County Council would embark on any major schemes. Few of us expected to be graded as Consultants and were deeply concerned as to the likely position of the hospital and ourselves under the new service. Eventually however all was well and the hospital once again began to move forwards. To my great personal delight I was relieved of all administrative responsibilities and was able to return once more to the surgical wards.

Talking of 'administration' reminds me that the word was never heard in the old days and life was much simpler. Any new project involving staff or buildings was roughly drafted as a sort of 'white paper' which was circulated among the staff concerned for criticism and comments. Finally after a friendly conference, a few letters between the county medical officer and myself would nearly always bring the scheme to fruition without the necessity for interminable committee meetings.

From an official list which has recently come to my notice the chief structural improvements during these years appear to include the following:-twin theatres, out-patient department, social centre, phoenix centre and the postgraduate medical centre. My own personal view of the gradual changes under the NHS was first and foremost the establishment of well defined departments with the appropriate Consultant, Registrar and House Officer staff together with much needed equipment.

Finally and most important of all, I would like to express my very sincere gratitude and affection for the several thousands of medical, nursing and ancillary staff who so ably and willingly assisted me in the running of the hospital over a period of thirty-six years - many of them remaining with us until their retirement.

John F Hackwood

LOCKSBOTTOM

Workhouse to Hospital

The old Farnborough Hospital at Locksbottom developed from the Bromley Union Workhouse, that opened in 1844.Over the first hundred years the workhouse grew in size to meet an increasing number of elderly, chronically ill and mentally ill residents plus children. In 1873 it provided a home for 420 residents and by 1910, 694 residents of whom only 23 were able bodied. An indication that as the years progressed the workhouse was becoming more of a hospital was the introduction of nursing staff in 1908, and by 1923, the appointment of two doctors.

Although by 1928 it was in effect a hospital rather than a workhouse it was not until 1936 that it became formally titled ‘Farnborough County Hospital’.

Then in 1948 it became part of the National Health Service and was renamed ‘Farnborough General Hospital’. Its main purpose was to provide operations and maternity services. The chapel still had an important role to play providing appropriate services to the needs of patients and staff. In the later decades of the century baptisms were still recorded in the chapel.

Then, by 2003, Farnborough Hospital was no more and had been replaced by the new Princess Royal University Hospital, now providing a broad spectrum of services, including accident and emergencies. The chapel, however became redundant, owing to an all faith provision being included within the new hospital building and reflecting the multi-ethnic community it now serves.

Well not quite redundant Although its religious service may no longer be required, the chapel has continued to serve the community as the Primrose Centre. This is a registered charity that provides complementary therapy, counselling and advice to support those affected by breast cancer. The external structure remains very much the original chapel of 1844, but internally it has been tastefully designed and decorated to be both welcoming and supportive to those who are initially shocked and distressed by their diagnosis as they journey through their treatment.

Bob Donovan