STORIES BEHIND THE WAR MEMORIAL - 2

This article was written in 2016 to mark the 100th Anniversary of the

Battle of the Somme. It narrates the stories of three more Farnborough

people who fought in the battle.

When I started writing about the Battle of the Somme, and how it related to the parish, I noted that eight names on the War Memorial corresponded to approximately the right dates and locations for the campaign exactly a century ago. Five of these names we have already explored and connected to the battle,see Stories behind the War Memorial - 1 the other three however proved far more interesting.

Although at first sight they

appeared to be connected to the Somme, my investigations revealed other

details and information which suggested otherwise and remind us that

this was not the only battle being waged by the British Army in 1916.

Sapper Arthur George Kidd,

Sapper Kidd service number 1687, served in the Royal Engineers and was 37 when he died. His parents, George and Harriet Kidd, lived in Farnborough – although I have so far been unable to find their address in the village.

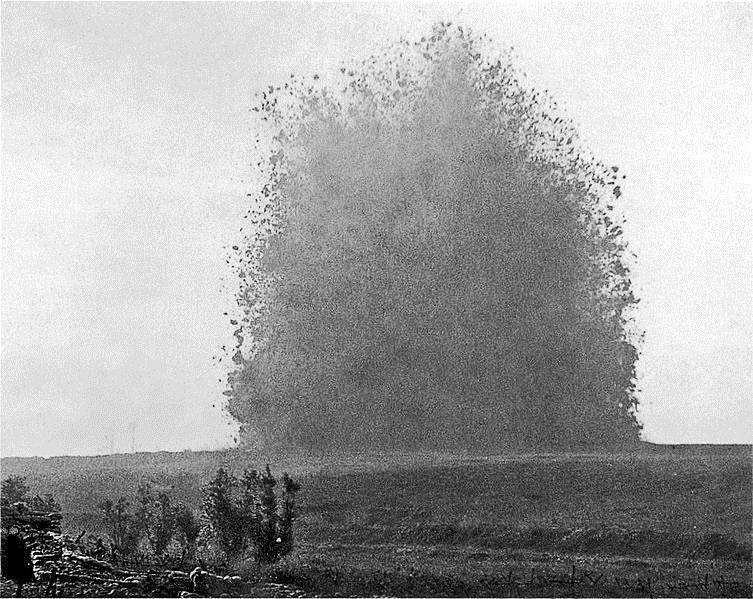

Over roughly a third of the British section, a lot of the infantry used tunnels and saps to pass underneath no-man’s land to surprise the German defenders. In addition, many other tunnels were dug under the German positions to place giant mines and assault weapons like the Livens Flamethrower where they could destroy the enemy trenches.

For this work large numbers of sappers were required, and so it seemed plausible that Arthur Kidd may have been involved in, and died as a result of, these subterranean operations.

|

By interrogating the usual web sites I was able to discover

that Sapper Kidd was a member of the 941st Field Company of the Royal

Engineers. This did not prove particularly useful as I then discovered no references whatsoever to a unit of that name. There was, however, a 491st Field Company which was attached to the 5th Division. |

This division was not deployed to the Somme area until the

second half of July, prior to that it was deployed to the north around

Arras. This was an area of major tunnelling operations which would bear

fruit the next year in a successful British offensive. It is

therefore possible that Sapper Arthur Kidd was involved in operations in

the Arras area of the front when he was killed, coincidently, on the

same day as the start of the great Somme Offensive.

Private Albert Victor Goodchild

Private Goodchild, service number 12802, was serving in the 1st Battalion the Royal West Kent Regiment (1RWK) when he was killed in action on the 11th of December 1916. When first looking at the war memorial I noted that the place specifically given was Beaumont Hamel, which immediately stirred my interest. Beaumont Hamel was an important German position during the Battle of the Somme which held out almost to the end of the campaign. As a result I was confident that Albert Goodchild had been a British soldier on the Somme.

From that point onwards however my investigations started to unravel. Looking through the war records for the Battle of the Somme I noted that it ‘officially’ ended on the 19th November 1916, almost a month before Albert’s death. In addition, the capture of Beaumont Hamel was achieved just under a week earlier by the 51st Highland Division. To make sense of this I next examined the combat records of the 5th Division and discovered that it had been withdrawn out of the Somme theatre of operations in early October 1916 and moved northwards to Festubert in the Arras area. The division was involved in some fighting in this area at the beginning of December 1916 so it is possible that Albert Goodchild could have been killed there.

|

|

| Lancashire Fusiliers at Beaumont Hamel | Vickers machine gun teams |

However, the war memorial is very specific about Beamont

Hamel and I have no reason to doubt this piece of information. It is

therefore just as possible that part of the 5th Division may have been

transferred back south as ‘reinforcements’ at the time in question. By

December 1916 many of the British divisions on the Somme were

under-strength and in dire need of extra troops. Having been rested up

north for a month it would have made sense to send detachments south to

the Somme – although this is just speculation on my part. However, if

this was the case then it’s quite possible for Private Albert Victor

Goodchild to have been posted to Beaumont Hamel at the time of his death. It was an important position

and the Germans tried on several occasions during the winter to try and

recapture it, without success. Albert Goodchild may well have died in

one of these defensive battles.

Private Allen William Smith

Private Smith was by far the most interesting and elusive of the names on the war memorial that I ‘connected’ with the Battle of the Somme. My initial trawl of the computer web sites confirmed that he was a private in the Machine Gun Corps (MGC) with a service number 65459. Born in 1886 to Eli and Elizabeth Smith he was 31 when he died (we will get to the mathematics later). The records show that he lived at 12 Cobden Road with his wife Jennie Smith. The records also listed his unit as the 202nd Company MGC. The Machine Gun Corps was a formation raised early in the war to meet the demand for large numbers of machine guns in the British Army. To save money before the war, the Government had limited each infantry battalion to just two machine guns (an attempt by Haig to get this increased to six in 1912 was blocked on financial grounds). This proved insufficient and so by 1916 each brigade was assigned a Machine Gun company with sixteen Vickers medium machine guns to provide additional firepower.

Faced with these apparent contradictions I delved back into the records and searched for more evidence.

The 202nd Company MGC was assigned to the 59th (2nd North Midland) Division as part of its ‘support arms’. Elements of the company would be allocated to the division’s brigades according to operational needs. The 59th Division was an interesting formation. It was mostly made up of men who volunteered to serve in Kitchener’s new army to defend the UK, but who then did not volunteer to serve overseas. As a result they could not be sent over to France and instead formed part of the Home Forces, freeing up other units for the Western Front. For the first two years of the war it was the ‘mobile division’ guarding the East Coast against invasion. However in April 1916 the 59th Division was despatched to Ireland to combat the Easter Rising. The division returned to England in January the following year, and that is when the 202nd Company MGC first appears on its order of battle on the 20th January 1917. By this time conscription had been introduced and the 59th Division had lost its ‘home service’ status.

The division left for France in February and was immediately deployed to the Western Front. It first saw action in April 1917 following up the German Army as the latter withdrew to the Hindenburg Line. It then was deployed into Ypres area of the front and took part in the 3rd Battle of Ypres. It was during this period that Private Allen Smith fell in action.

Andrew Bailey

FARNBOROUGH VILLAGE