THE FOX FAMILY AND EDUCATION

This article has been developed from Chapter 3: Involvement in Education.of

'Michael Frederick Kempton U8737912 A826 - a dissertation submitted for an MA degree in History in 2014'.

It is reproduced here with the permission of the author.

Introduction

This article concerns the reasons for the establishment of Green Street

Green elementary school by the Fox family in 1851, its involvement with

it and another in Farnborough parish. In Chelsfield, the involvement of

the Nonconformist Foxes with a third school is explored.

The impact of the Fox family’s involvement in education on the local community, and its extent compared with that of other paternalistic employers, is investigated. Parents’ reasons for sending children to the schools are explored. Sources concerning school inspections, funding, curricula, management and the influence of religion in the three schools are used.

School Provision

Apart from a school constructed in a ‘model village’ by Free, Rodwell at Mistley in Essex, similar in size to Fox’s brewery, it is difficult to find school provision in or near Kent by brewers in the period.Before 1851, Green Street Green children were unlikely to have had schooling unless they travelled two miles to Chelsfield or one to Farnborough. From 1835 the Chelsfield school was funded by subscriptions, largely by the major landowners the Warings, and the Rector, and fees (‘school pence’).

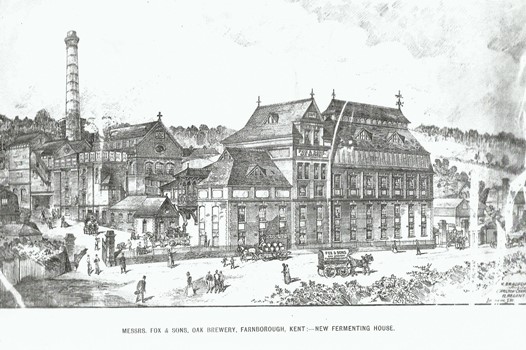

Farnborough had two Dame schools in early to mid-nineteenth-century, one near the church later becoming the elementary school. The Dame schools were funded by Sir John Lubbock, brewer John Fox, and fees, and supervised by Lubbock’s wife and daughter. As Green Street Green grew with the brewery’s expansion, John Fox believed a school was needed for employees’ children and others living locally. He needed to establish a settled, cooperative, current and future workforce with a school which would teach future workers to be respectful, cheerful, hard-working, loyal, pacific and religious.

Fox earmarked some Oak Farm land by the brewery and started planning the design and funding, and applying for the necessary permissions. The application, by John, sons J.W. and T.S. Fox and four gentry promoters, dated 10 January 1851, was from ‘the chief promoters of a subscription towards the building of a school to the Lords of the Committee of Council on Education, for 25 boys, 25 girls and no infants, in the one mile square hamlet, population 300, chiefly agricultural labourers. It stated that the education of the poor was sorely neglected, the promoters intended to appoint a master and mistress and an annual sum of £40 was to be raised for school maintenance, a Government stipulation. Sarah Fox, John Fox’s daughter-in-law, was appointed to conduct all correspondence. The reason given for establishing the school exhibited concern for the lack of educational opportunities for local poor children.

Earlier schools had poor building fabric, equipment and teaching competency, therefore the Council on Education, on granting provisional approval, required details of promoters’ proposals before giving final approval and bestowing any grant. Plans detailing internal and external materials were submitted specifying room sizes, drainage method, boundary walls, ventilation, heating and opening windows. Receipts, in hand, promised or expected totalled £167 5s 6d and proposed expenditure £245. The grant application was for the deficiency of £77 14s 6d. Their Lordships granted the application on 30th August 1851, but for only £42 10s. A Certificate of Completion was ultimately sent to the Committee, stipulating that the promoters had met the shortfall.

The 1870 Elementary Education Act permitted elections among parish ratepayers to form a School Board, with local educational powers. Farnborough ratepayers unanimously agreed to form a Board, and on 17 June 1871, Sir John Lubbock was elected Chairman, together with five Board members, including J.W. Fox. T.S. and J.W. Fox agreed on 1 February 1872 to transfer Green Street Green School to the Farnborough Board. The Managers also confirmed that the Archbishop of Canterbury, as Trustee, agreed the transfer.

A £2,000 mortgage was raised to build a larger Farnborough School in 1873. In October 1886 Thomas Fox Senior died and it closed for an afternoon to allow children to attend his funeral. In 1889 overcrowding compelled the Government Inspector to threaten withholding the grant. The Board, from 1886 including T.H. and Walter Fox, raised a further mortgage of £1,220 and the school was extended. The brothers provided entertainments for Farnborough schoolchildren, and Rachel and Elizabeth Fox provided knitting and needlework prizes, over many years.

Sarah Fox ‘was associated with Green Street Green School for many years’ Log Books between 1887 and 1889 confirm her commitment to the school, and that of nephews Walter and T.H. Fox, one or both checking and signing the registers, usually weekly, confirming their accuracy.They reported the results of the Inspector’s annual examinations in reading, writing, recitation, grammar, arithmetic, geography and needlework.

Capitation Grants, of five shillings for boys and four for girls, for rural schools were introduced in 1853. They depended upon attendance on 176 days each year, reduced from 192 when children’s harvest involvement was stressed by the Bishop of Salisbury, upon teachers maintaining registers and pupils passing Inspectors’ examinations. The Green Street Green grant for 1889 was £68 12s 6d.

The Chelsfield ratepayers did not form a Board in 1870. They, but largely Squire William Waring and Rector Folliott Baugh, continued supporting the Church School. However, in 1884 Waring, resenting bearing much of the financial burden, called a ratepayers’ meeting for 16 May. A Board was elected, meeting on 31 July. 35 Non-Anglicans could then serve the school, and Nonconformist farmer W.B. Fox became a founder member. His sons William and Edwin, both Nonconformists, also served as managers and William later as Chairman.

Fox family involvement varied at the three local schools. At Farnborough, funding and management before 1870 were shared with Sir John and Lady Lubbock, who managed day-to-day matters with an emphasis on religious and moral instruction. At Green Street Green, before 1870 the Foxes had freedom to appoint teachers of their choice, despite National Society ties, thereby having an element of control over the curriculum. At both Farnborough Board schools, instruction in discipline and good behaviour was valued by potential employers the Fox brewers.

After 1870, family members continued to be closely involved with the schools in various capacities, providing treats and prizes and giving generously of their time. At Chelsfield, W.B. Fox and sons were not permitted involvement in the church school’s management until the Board was formed in 1884, to which they were elected and William became its first Nonconformist Chairman in 1899.

So what were parents’ motivations for sending children to school?

Parents before 1880 were not obliged to send children to school: ‘school attendance in England was strictly voluntary; a combination of private enterprise, limited public funding, religious organizations, and miscellaneous philanthropy provided elementary schooling to those who wanted it’. Moreover, the Newcastle Commission in 1861 found that 1850s child wages ranged from two to four shillings weekly, a considerable addition to the agricultural labourer’s family income of between nine and fifteen shillings.

Earnings were one incentive for parents to keep children from school. Others included poor opinions of teaching standards and curriculum, and hostility and apathy towards education.

A third of working-class parents continued choosing Dame schools until 1870, even with public schools nearby. Some parents believed private schools were more ‘genteel’. However, the reality was that flexible hours of attendance, the working-class nature of those running them for the working classes, and the feeling that they had influence over the dames, were more important to parents, and that they might see education as a means of betterment for children, a feeling that grew stronger as the century progressed.

Attendance figures for local schools are as follows:

| 1856 | 1857 | 1861 | |

| Green Street Green

National School |

55 out of 74 (74%) | 55 out of 69 (80%) paying 2d. a week | |

| Chelsfield Church School | 51 out of 84 (61%) paying 2d. 1 week | ||

| Farnborough 'Church School' (ref. Diocesan Inspector 1851) | 45 out of 76 (59%) fees unknown |

Higher attendance at Green Street Green was attributable to its proximity to both parents’ housing and workplace, and its popularity. Chelsfield and Farnborough schools’ attendance suffered through scattered rural populations, particularly in poor weather. Inspector Smith mentioned serious difficulties with agricultural work absences at Chelsfield on 1 July 1851, and school log books (available from 1883-1906) highlight fruit-picking absences on 13 July 1883, 1 July 1884 and 3 July 1885 (50% absence). In September 1886, the school was closed for three weeks for hop-picking. On 24 September 1888, Green Street Green School closed for an extra week, as over 60 pupils were away hop-picking.

Epidemics of measles, whooping cough, croup, diphtheria and scarlet fever caused many absences, and sometimes school closures, as did extreme weather conditions. Lack of suitable clothing and footwear, and ‘minding the baby’, also resulted in absence. Irregularity and non-payment of fees sometimes led to dismissal

Parents also caused difficulties for schools: T.H. Fox recommended that the Master took

out a summons against a parent for insulting him before the whole school.

Fees were used for schools’ upkeep. Prizes, treats and entertainments were provided by the managers. Although children’s seasonal agricultural work still provided a necessary supplement to family income, parents were coming to realise that education improved employment prospects. The proximity of Green Street Green School to brewery and housing, as well as educational standards were attractive to existing brewery workers and those seeking employment.

The influence of religion in local schools In National and British Schools, teaching religion, morality and improving children’s literacy standards were the main objectives. Readers teaching morals and religion were distributed to schools, supplemented only by the Bible, religious tracts and morality tales, designed to ‘improve’ the working-class child. Although both referred to the poor, there were differences in tone between National and British texts. The latter encouraged thrift and diligence as means of advancement, while the former devotion to hard work and acceptance of position in life.

By 1851, readers had changed in emphasis. While the Scriptures remained, secular subjects like grammar, arithmetic, geography, history and political economy were added. In 1861, the Newcastle Commission required elementary education to include the reading of a ‘common narrative’, writing a legible letter and understanding a shop bill. In 1862, grants were paid only for examination passes in reading, writing, arithmetic and needlework. Indicating a requirement for broader knowledge, history, geography and geometry were added in 1867.

The Diocesan Inspector of Schools, between 1851 and 1872 was B.F. Smith, whose reports directly to the Archbishop were under the auspices of the National Society. The regional state of elementary schooling in West Kent was detailed in his 1851 general report dated 28 October on 37 schools in the Shoreham Deanery, including Chelsfield and Farnborough. Many schools’ standards needed improvement. In his report of 10 February 1852, he informed the Archbishop that the most important factors sought were good order and discipline, intelligence, personal neatness and cleanliness, religious instruction and general moral tone, all attributes important to employers like John Fox. No mention was made of academic subjects.

Between 1851 and 1872 Smith visited the Deanery in 1851, 1854, 1857, 1860/1, 1871 and 1872. He inspected Chelsfield, the only local church-related school, ‘supported by the Squire and Rector conjointly', on every occasion. In reports of 7 December 1871 and 26 November 1872, the only subjects mentioned were religious, restricted in depth in 1871 owing to a serious outbreak of epidemics; in 1872, above average religious knowledge was learnt by rote and repeated well by older children, and scripture learnt by the infants was ‘readily repeated’ and texts ‘well understood’. However, in 1851 reading and writing had been average and arithmetic ‘as bad as can be’; girls were taught to sew, darn, make and mend clothes, but not to knit; secular and church history, geography, drawing and singing were also taught. Things had improved by 1854, when arithmetic was better, writing and spelling creditable and reading better for secular class books.

The Curate and daughters of the Squire and Rector gave assistance regularly at the school, but Nonconformist farmer W.B. Fox was permitted no involvement. Farnborough School was inspected in 1851, 1854 and 1857. Smith stated in 1851 ‘supported by Sir John Lubbock’ and ‘though not under the superintendence of the Clergyman, the Down and Farnborough schools are to all practical intents Church Schools’. Short reports were quite favourable, emphasising high standards of neatness, cleanliness and propriety of behaviour.

John Fox was a patron and Sarah Fox taught at Farnborough and ‘supplied calico for the needlework class and wool for knitting’. John Fox’s new school was to be ‘in connexion with the Church of England and called the Green Street Green School….and nearly all the families of the labouring population within three miles of the school are members of the Church of England’. Fox conveyed the land to the Archbishop of Canterbury on 22 September 1851, stating that it was ‘for the education of children and adults, or children only, of the labouring, manufacturing or other poorer classes’. Also, ‘no books were to be used that can be objected to on religious grounds’, teachers should be members of the Church of England, could be dismissed for unsound instruction, and Diocesan inspections had to take place.

With no church affiliation, the school was inspected only in 1857 and 1861. The 5 February 1857 inspection described a ‘commodious room, well warmed with parallel desks’. Parallel desks facilitated supervision by the monitors. The first class ‘read and wrote fairly and had some knowledge of geography. In spelling and arithmetic they were very backward’. He described their knowledge of scripture, history and the catechism as fair, but they were ‘imperfectly acquainted with the rudiments of Christian doctrine’. He pronounced singing as their strong point, confirmed that the school was maintained by John Fox and that it ‘enjoys the superintendence of his family’. Sarah Fox helped to manage the school and often taught there. Soon after the Green Street Green School managers agreed that it should come under the Archbishop’s auspices, conflicting actions occurred, without complaint from the Diocesan Inspector. The managers appointed school mistresses, in 1857 and 1860, certified by the British and Foreign School Society, originally nondenominational, but later representing Nonconformist interests. The Inspector noted this in 1857 and 1861, without adverse comment. In 1861 the new mistress had even improved the ‘discipline tone and religious knowledge of the children’.

Sarah Fox asserted that the school was not affiliated to the National Society nor united to the Diocesan Board. The Inspector reported signs of improvement in the relatively low secular attainment of pupils, perhaps indicating his increasing interest since 1851 in non-religious subjects. The Managers, in risking upsetting the Anglican authorities, may have preferred the British Society’s broader subject range which improved employment prospects for children.

At Green Street Green, the weekly fee was twopence per child and a penny halfpenny for related children. Six years earlier, 75% of children nationally were paying up, to twopence. Schools’ income was important, and for Green Street Green and Chelsfield it featured in Diocesan Inspector Smith’s reports, which for 1851 also contained details of the 37 schools in that Deanery: This showed that local schools were not endowed; fees at Green Street Green almost halved as a proportion of income in 1861, as pupil numbers remained static prior to the brewery’s major expansion in 1866 and new housing in 1867; lower fee income meant higher subscriptions from the Fox family. Also in 1861, clergyman and Squire had to produce even more funding at Chelsfield.

Elementary education improvements were underpinned by legislation from 1870 onwards: attendance became compulsory in 1880 for children between five and ten, rising to eleven in 1894, twelve in 1899 and fourteen in some areas in 1900; school attendance officers were appointed; free elementary education was introduced in 1891.

The 1902 Act abolished School Boards and established Local Education Authorities, controlled by County and Borough Councils, thereby standardising education.

Conclusion

John Fox founded Green Street Green School in 1851 for several reasons. Improvements to the infrastructure were required to attract the workforce required for brewery expansion. These included a school for workers’ children. As Fox, a local landowner, required them, he had to bear the costs. From the middle-classes, he strived to ‘improve’ the working- classes, instilling them with his moral and religious values. This could be achieved through education, ensuring that children were gainfully occupied, perhaps becoming future workers accustomed to the order and discipline required in the workplace.Anglican members of the Fox family were able to influence education. Initially affiliated to the National Society, Green Street Green School effectively became nondenominational enabling managers to broaden the range of subjects taught. The Diocesan Inspector approved this and even praised religious teaching after the change. He seemed more interested in Chelsfield church school, in which Nonconformists W.B. Fox and sons were initially unable to participate. He found little to criticise, or even comment on, at the Lubbock and Fox quasi-church school at Farnborough.

He praised the management of all three schools and accepted funding arrangements. Teachers at Chelsfield were trained under the National System, at Green Street Green the British System, and before 1870 at Farnborough were largely untrained. Throughout many legislative changes after 1870, Fox family members altruistically participated in voluntary capacities in the three local schools: three sons and four grandsons of John Fox were managers and several female relations dedicated to teaching, supervisory duties and prize-giving.

As a family, their commitment to education, for their wealth and class, was exceptional, even among philanthropists

THE LOCAL AREA

Attitudes to Education in Britain

Before 1836, educating working-class children in Britain was controversial. Many churchmen, farmers and factory owners opposed education, believing that their plentiful supply of inexpensive labour would disappear if education fostered working-class aspiration to betterment, causing resentment of ‘the state of life to which God has called you’.A small minority of employers in all districts took an active interest in educational provision, both by generous subscriptions and by personal influence, but farmers, particularly at harvest time, strongly opposed education.

Children’s wages were often essential for family support. Some believed that literacy would enable the working-classes to absorb subversive publications leading to unrest, while others believed education, including the instillation of middle-class values, would act as a measure of social control.

By 1836 policy-makers held the latter view. Monitorial schools run by the Anglican National Society and the nondenominational (later Nonconformist) British and Foreign School Society, and private Dame and Common Day Schools, provided most education then for working-class children.

Dame schools remained popular with the working-classes, as they ‘had no taint of charity or of heavy social control by the churches’.

The societies controlling monitorial schools used older children as monitors, teaching the younger while supervised by the schoolmaster.

Reverend Andrew Bell (Anglican) who founded the National Society and Joseph Lancaster (Quaker) founder of the British Society quarrelled, for years competing to build as many elementary schools as possible. This contest was further stimulated in 1833 when Parliament subsidised school-building, granting £20,000 conditional on managers matching the grant and being members of a Society. This rose to £193,000 in 1850. Societies also established training facilities for teachers.

As an example, Jeremiah James Colman founded a school at Stoke Holy Cross in 1840, which was relocated to Carrow in 1857 soon after the Colman’s factory was moved there. He invited all employees to send their children to the school, which opened with 23 pupils. All costs were met by Colman and his Partners, although fees of a penny a week and a halfpenny extra for another child, provided money for prizes. Colman established the curriculum, including reading, writing, spelling, arithmetic, grammar, non-sectarian Bible studies, history, geography and drawing. Too small, the school moved to Carrow Hill in 1864. In 1870 pupils numbered 333, and in 1891, before which the company had borne all costs, it became free and a government grant was sought. Pupils then numbered 637.

Nonconformists, Colman and his wife Caroline believed that children’s education should improve their employment prospects and help them rise in the social scale. Therefore, after 1864, practical subjects were introduced, including gardening, beekeeping, basket weaving, leatherwork, first aid and nursing.

School rules were fair but strict, with dismissal for irregularity, and dishonesty, for which all family members were expelled, but no corporal punishment.