SUNNYSIDE

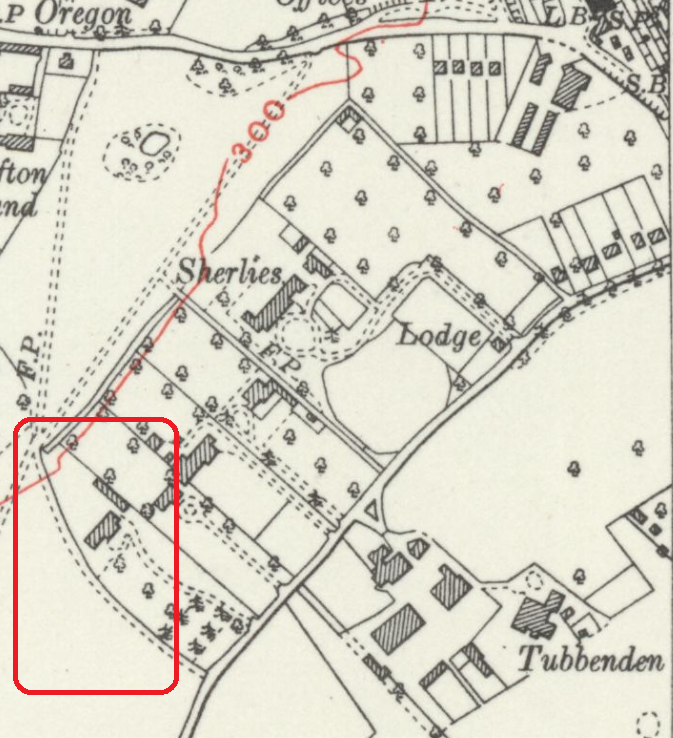

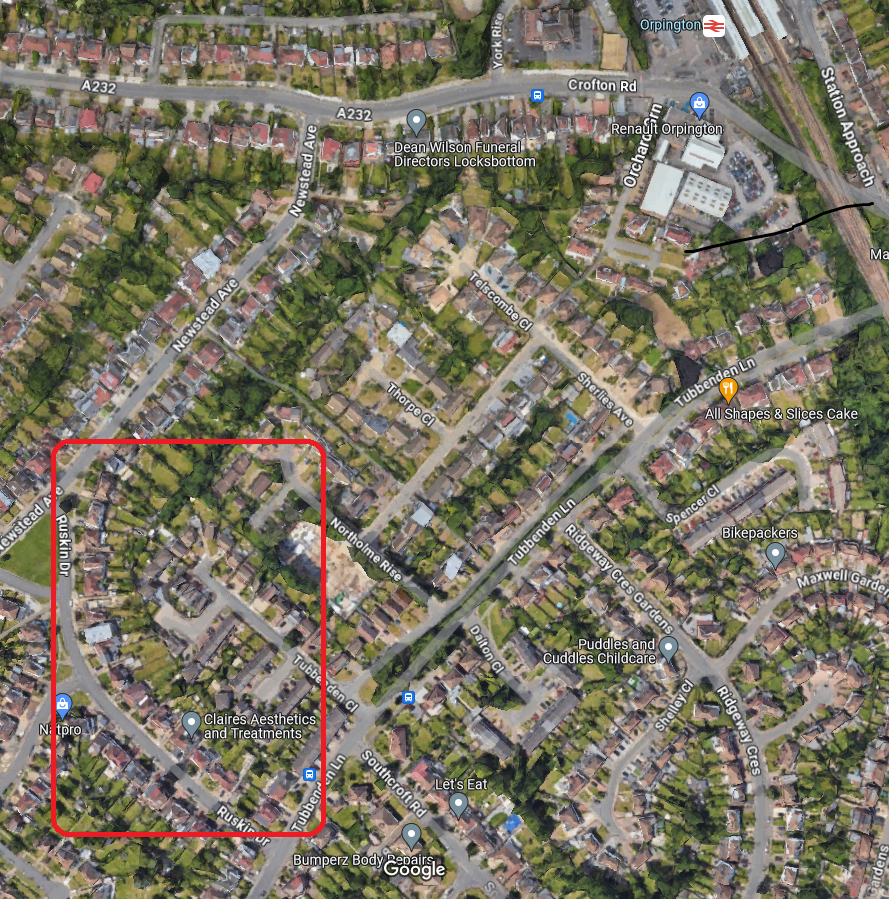

Sunnyside was the name of a large house on the north side of Tubbenden Lane, which leads from Orpington to Farnborough. Built in the 1870s, it was one of five of similar age occupying prominent and deep plots on the south facing slope, opposite the house and once considerable estate known as Tubbendence.

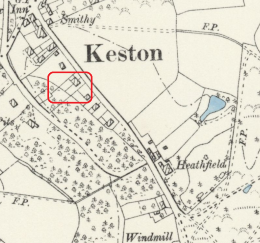

The first map below shows the houses as they were in the 1930s, with Sunnyside marked, All of these houses are now gone. The Google Streetview capture shown alongside it shows the same site today, with again the former location of Sunnyside marked. Click on the streetview map to enlarge and navigate. The former footpath to the western boundary is now a road using the same alignment, named Ruskin Drive.

|

|

The accounts below and on the side panel are taken from the website George Allen of Sunnyside and are reproduced here by permission of the author, Paul Dawson. Paul has been in communication with a recent owner of Heathfield Cottage, the family's former home in nearby Keston, referenced in the first paragraph below. The owner was able to confirm the Allen provenance. Unlike Sunnyside, Heathfield Cottage still exists, see the panel to the right.

Sunnyside, Orpington The home of George Allen from 1874-1907

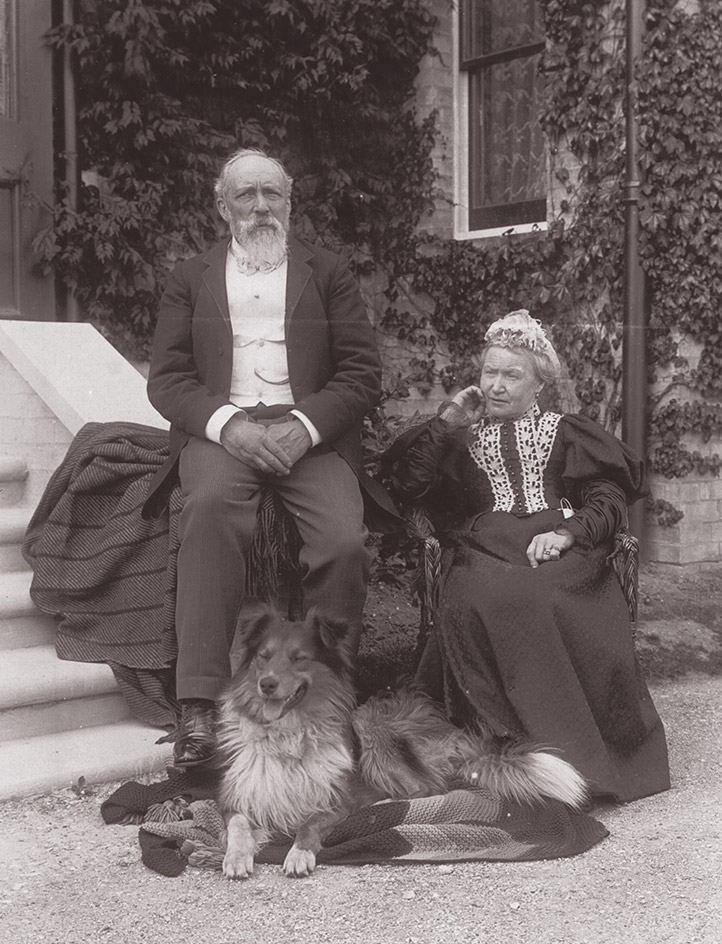

By 1873, Allen’s home at Heathfield Cottage, Keston, had become very crowded; his family now included eight children ranging from Grace (b.1858) to John (b.1871). The additional need for storage space to hold Ruskin’s publications prompted an attempt to rent the adjoining land in order to erect a building that might provide storage and working space, but the negotiations with the owner were not successful, and whilst out walking with his son William in the summer of 1872, George Allen looked at a plot of land for sale at Orpington on a fine south-facing site not far from the railway station.Correspondence with the owner, a Mr May, followed, and in January 1873 the deposit was paid and the land secured in Ruskin’s name with a loan made by him to Allen for the land and a house to be built upon it. An architect cousin was engaged to design a house to stand on the site, and the completed home ~Sunnyside ~ was occupied by the Allen family on February 4th 1874. Standing at the end of a winding gravelled driveway that terminated in a carriage sweep, Sunnyside was a fine example of a nineteenth century villa with its terraced lawns, tennis court, bowling green and rose garden. It was built of white brick, over which creepers were allowed to spread through the years.

|

|

| Sunnyside from the North | Sunnyside from the South |

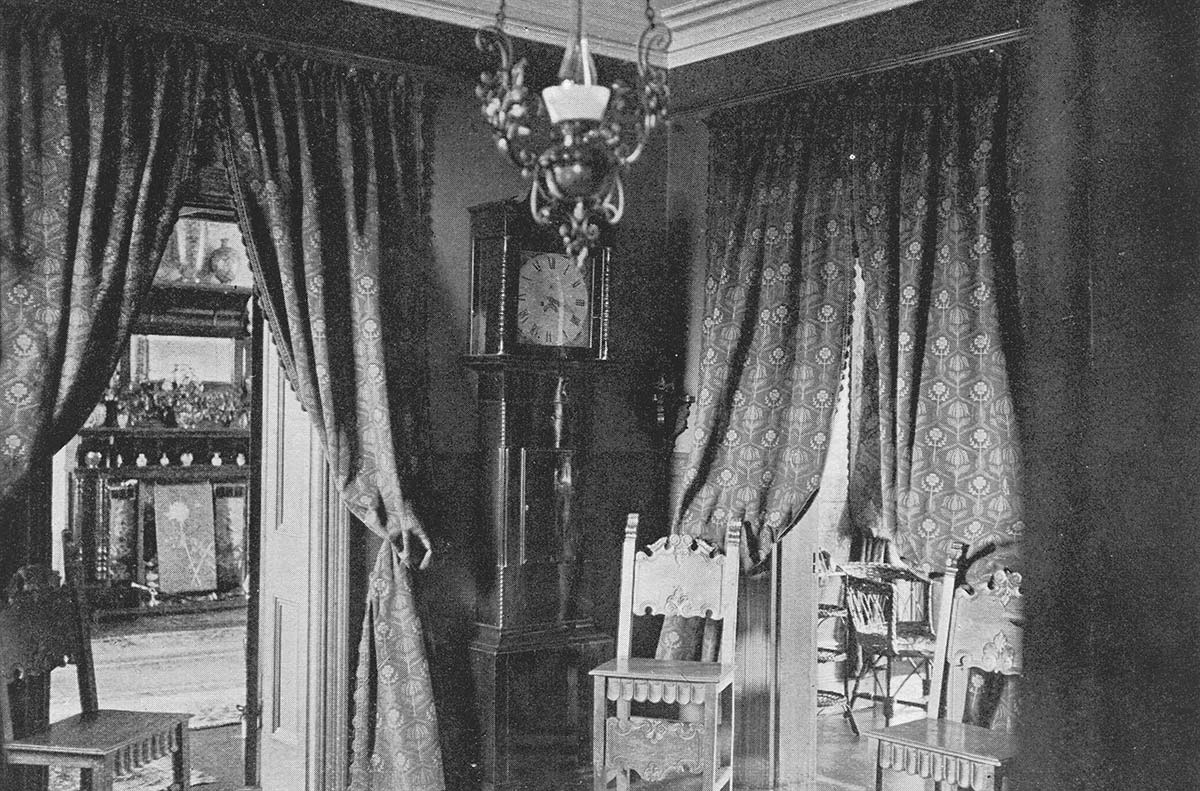

The five steps up on to the front porch led the visitor to the front door, which opened into a square entrance hall with a polished oak floor. A four-panel door on the right led to the dining room, and a further door on the left led into the large drawing room with its imposing over mantel and parquet flooring. From here, double doors led through to the library on one side, and into a large conservatory on the other. Also on the ground floor, of course, were the ‘domestic offices’ comprising the kitchen, scullery, pantry and lamp room. On the first floor were eight bedrooms, the largest having a dressing room attached, and a bathroom. On the second floor were a further six bedrooms and two storerooms.

Between 1880 and 1883, George Allen spent a further £3,500 on enlarging the house to accommodate his now grown-up family. Of his eight children, five never married and were resident at Sunnyside for much of the time. There was also the ever-increasing need for storage space to hold the stock-in-hand of Ruskin’s published titles. A detached engraving studio with improved lighting was built on the eastern side of the main house, which incorporated a large storage area.

|

|

| The Entrance Hall | The Drawing Room |

In 1883, Ruskin paid his first visit to Sunnyside. Surprising, he waited nine years before he called to see what had become the heart of his publishing commitment and the home of his loyal assistant of nearly thirty years. As Sunnyside was also a project that he had financed, and to which he had reputedly offered suggestions for its design, his visit was long overdue, and although just a brief call, it caused some excitement among the Allen family. Grace Allen recalled that occasion in her notes:

During that same autumn we had the fulfilment of Ruskin’s promised visit to us at Sunnyside, on October 21st, 1883. It is true it was only a call, made in an interval of his stay with Lord Avebury (then Sir John Lubbock) at his High Elms home near Downe, some two miles away.

A further visit followed in 1885, when Ruskin lodged at Sunnyside. William Allen noted the following in his reminiscences:

On May 15th and 16th 1885, he came again and stayed two nights. During this stay, we used to try to get him to come and help, but he said he hated parcels, and didn’t believe anybody really wanted to read all those books; he preferred us to go with him to the flowers and woods.

He was then preparing and working upon his autobiography, Praeterita, and during afternoon tea with us, used to read some of the manuscript of this work and chuckle over it. In the evenings we generally sang to him, and he much enjoyed a humorous song called “Old Timber Toes” sung by me, which had a vogue in those days. He made himself quite one of the family, always retiring to his room soon after his cup of tea, and thoroughly enjoying our family dinner at 7 o’clock.

Sunnyside, on the outskirts of Orpington, with its population in 1874 standing at just over 200, was just a few miles from Sir John Lubbock’s High Elms estate. Only a short distance further on was Downe House, the home of Charles Darwin, which the Allen family are known to have visited; and whilst staying only ten miles away at Keston Lodge, Carlyle drove a pony carriage over to Sunnyside in 1875. So, although in the middle of a country field, as the trade press sarcastically remarked when George Allen’s change of address appeared, Sunnyside was not completely isolated or starved of intellectual input.

Ruskin’s last recorded visit to Sunnyside occurred in 1888, during his prolonged stay in Sandgate. Whilst visiting London from Sandgate towards the end of April, he travelled down to Orpington on the 30th, where he stayed with the Allen family for two days. Although builders were working and the house was in a state of upheaval, he said on leaving that the place felt more like home than any other he had been in for a long time, and he made a special request that the new arrangements in progress should include rooms to be reserved for himself whenever he felt he needed a change of scene. But with his failing health, he was never to visit Sunnyside again.

The executors of George Allen’s estate put Sunnyside up for auction, the date being set at June 17th, 1910, through the agency of Harrods in Brompton Street. The date of the eventual sale and removal of the Allen family was 1915 ~ five years after the date given for the auction. Correspondence from William Allen, some of which is held in the Business Records of George Allen and Co., give his address throughout the period as Sunnyside, and searches in the Orpington Street Directories show no independent addresses for the Allen children prior to 1915. It is fairly safe to conclude, therefore, that for some reason the intended sale was unsuccessful, or that the property was withdrawn from the market.

The incoming owner of Sunnyside in 1915 was John Hunt, the county treasurer. He renamed the property Ruskin House, which did not please the Allen family. Whilst the children of George and Anne Allen had a great respect and many fond memories of Ruskin, they often felt that their father’s own considerable achievements were never out of Ruskin’s shadow. Sir John lived out his remaining years at Ruskin House, and when he died in 1945 it once more came onto the market.

The house was bought by Kent County Council to provide temporary shelter for families who had been made homeless during the recent war. The accommodation it provided was on the basis of communal cooking and eating, utilising the generous kitchen and scullery area that had formerly been the province of the employed staff of both former households, but offering separate sleeping quarters. Bathing facilities on each floor were also shared.

The accommodation in 1945 consisted of a large entrance hall (which in George Allen’s day was a smaller hall and separate library, the dividing wall having been removed; the original large drawing room (32ft by 19ft) and dining room (21ft by 19ft).

The first floor now had seven good-sized bedrooms, one having been converted to a second bathroom. The top floor had a further seven rooms, one of the storerooms now being used as living quarters. The warehouse with its first floor engraving studio, which had been built at George Allen’s direction in 1883, had been converted to a six-bedroom cottage, providing ideal quarters for warden or caretaker.

Thus Sunnyside (or Ruskin House) developed and survived for another twenty years, still providing shelter for the homeless, but no longer the victims of war loss. It is quite clear from the council minutes that the house, approaching one hundred years old, needed a proper care and maintenance programme, and had become a burden to the council. Minor repairs were sanctioned if necessary. Caretakers never stayed long ~ there were constant and regular requests for transfers and new appointments.

A more ominous train of discussion began to regularly crop up at council meetings. In June 1961, the council discussed an application to purchase the frontage land at the edge of the Sunnyside plot, and requested a report on the desirability of selling the plot as a whole or in small lots. Just three months later, a funding application for improvements and decoration was approved, so it was unlikely that the house itself was due for disposal. In January 1963, a strip of land at the southern boundary was dedicated to the public highway as part of a road-widening scheme. In October 1963, the council once more debated the future of Sunnyside. Its form of communal lodgings was out of step with the move towards smaller individual housing units, but again a decision was deferred. Two months later, planning permission was granted for ten terraced houses to be built at the southern end of the plot. With the road already widened at the expense of Sunnyside land, development was beginning to take hold on the site.

By 1970, Sunnyside was standing empty and run down on a neglected site, but not until 1972 was it placed on the list of surplus properties for disposal. Similar properties in either side had already gone, replaced by housing developments, some dating from nearly ten years earlier. A new residential road, Tubbenden Close, was constructed alongside the northeastern boundary, incorporating an access road into the Sunnyside site. For a further year, it stood incongruously above the housing that surrounded it. It was placed on the open market, and in a climate of rapidly and erratically rising prices, it attracted considerable and varied offers. Withdrawn from the open market in favour of sealed tender bidding, the last reference in the council minutes occurred in April 1973, when the committee responsible were informed that the sale of the property known as Ruskin House to Falcon Developments (Guildford) Ltd., for the sum of £332,000 had been completed.

Shortly afterwards, Ruskin House (Sunnyside) was demolished and the site cleared, the last survivor of the buildings which were erected on those plots which George and William Allen walked to on that summer day, almost exactly one hundred years earlier. © Paul Dawson

THE LOCAL AREA

Heathfield Cottage, Keston

This was the home of the Allen family until they acquired the land to build Sunnyside, which they moved in to in 1874.

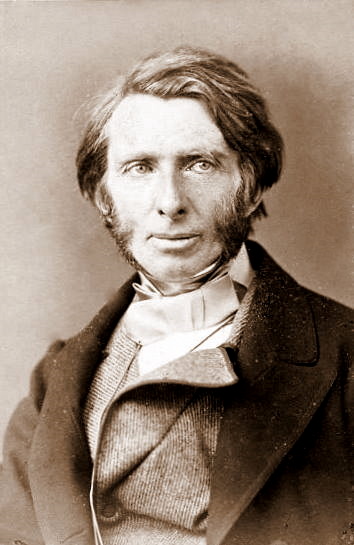

George Allen and John Ruskin

Because it is impossible to consider the life and achievements of George Allen without frequent references to John Ruskin, his considerable talents have often been overshadowed by Ruskin’s enormous presence.The renewed interest in Ruskin’s publishing methods offer the opportunity to examine George Allen’s role in that scheme, and to evaluate his significance in its success. Ruskin’s own words on George Allen in Praeterita serve as a good starting point for a brief outline of Allen’s life:

I took two pupils out of the ranks to carry them forward all I could. One I chose, the other chose me ~ or rather, chose my mother’s maid, Hannah, for love of whom he came to the college, learned to draw there under Rossetti and me, and became eventually Mr. George Allen of Sunnyside, who, I hope, still looks back to his having been an entirely honest and perfect working joiner as to the foundation of his prosperity in life. (Praeterita Vol. III, chapter 1)

A carpenter by training, George Allen was 22 years old in 1854 when he first saw Ruskin at the Working Men’s College. Having enrolled in the drawing class, he impressed Ruskin with his natural ability and shortly became one of the assistant drawing masters. In 1857 he left the building trade and became Ruskin’s full time assistant, where at his new employer’s instigation he learnt the skill of engraving under two contemporary masters of the art, Lipton and le Keux.

He accompanied Ruskin on several geological trips into the Alps, where his instinctive grasp of strata and formations proved a useful adjunct to Ruskin’s knowledge. He later went on to build up a significant collection of minerals, which was purchased by the Oxford University Museum after his death. But it is for his role in the publishing house of George Allen for which he is often best remembered, although it might be argued that even there he resided for many years in Ruskin’s shadow.

As his assistant, Allen had been involved with many tasks linked to Ruskin’s own interests and pursuits. He was with Ruskin during the cataloguing of the Turner Bequest in 1857, and also at this period furnished drawings for the illustration of Ruskin’s lectures. In 1862, with his young family, he accompanied him to the Savoy mountains for two years, during which time he was engaged upon a project to engrave certain of Turner’s drawings at their full size ~ this work being interrupted by various geological expeditions and visits to sites which Ruskin considered of vital artistic or architectural significance.

When recalled to England in 1864, Allen slotted back into his former role as assistant and engraver, making regular trips from his home in Keston to Denmark Hill, as and when summoned by Ruskin. It was such an occasion in December 1871 when Ruskin sent for Allen and announced that from the following month Allen was to act as distributor of his new pamphlet Fors Clavigera, and that the delivery from the printer was due at Allen’s home in just two weeks.

John Ruskin

When Ruskin decided to establish this radical, but in his view fairer way to publish his work, George Allen was merely the instrument of sale and despatch. But when, a few years later, he considered taking his existing works away from Smith, Elder & Co., it was George Allen who persuaded Ruskin of the advantages of keeping control of the copyright, thus controlling the reprinting of the earlier titles. Thus, his role as distributor became one of publisher, his responsibilities increasing. In later years, after Ruskin had held out for so long against the idea of cheap editions of his works, it was Allen who convinced him of the need to supply the new literate masses who were unable not afford the finely bound volumes currently available to them.

It will be seen that the relationship of master and pupil was slowly reversed. Allen’s business acumen provided timely reprints of Ruskin’s titles long out of print, and provided both ends of the book-buying market with what they desired. Whether it was luxuriously bound and illustrated volumes printed on hand made paper with no spared expense, or reprinted editions in simple but elegant cloth covered boards ~ George Allen could provide it, and in doing so, provided also the income that Ruskin would later depend upon. In the early days, he took his instructions from Ruskin, and would offer his own suggestions for Ruskin’s approval. By the time that Ruskin’s mental powers had faded, George Allen had assumed virtually all responsibility for decisions made by the much respected publishing house that carried his name.