THE FOX FAMILY - WORKERS' HOUSING AND RECREATION

This article has beendrawn from Chapter 4: Involvement in Housing and Recreation, of

'Michael Frederick Kempton U8737912 A826 - a dissertation submitted for an MA degree in History in 2014'.

It is reproduced here with the permission of the author.

Introduction

This article concerns the provision of housing and recreational facilities for Oak Brewery workers, an important part of Fox family paternalism. The motives behind these costly enterprises are explored, in terms of philanthropy, business and social reform of the working-classes.

The family’s motives are explored, using for comparison purposes secondary sources, including well-known employers’ model village schemes, provision by major industrial revolution employers such as ironmasters, and brewers, many of whose companies were of similar scale to the Oak Brewery. Titus Salt’s industrial settlement of Saltaire is used as an exemplary model village. For housing in sparsely-populated areas required for workers in rapidly expanding industries, examples are drawn from gas producers like the Gas Light and Coke Company, iron and steel manufacturer The Coalbrookdale Iron Company, three railway companies, Brunner Mond for chemicals and large brewing companies like Watney’s.

Housing in Farnborough

Construction of workers’ cottages was started in 1867 by the Fox family.

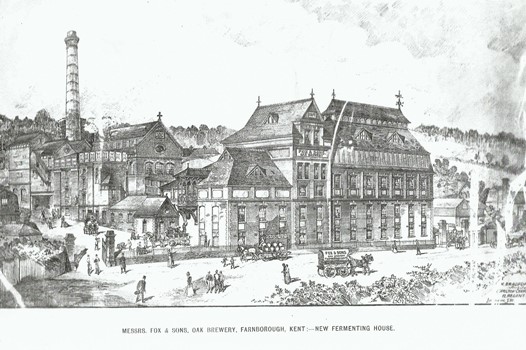

The year previously an additional fermenting block had been built,

requiring extra workers, some 27 by 1871. The 1871 Ordnance Survey map indicates that most of the thirty workers’ cottages had been built. Tied housing, and other employer-provided facilities, encouraged workers considering changing jobs for greater remuneration to balance this against losing housing and other amenities. However, as the Oak Brewery was the only large employer for several miles around Green Street Green, apart from farms with lower rates of pay, this was unlikely to occur.

It was observed of the employees that: ‘many…..have seen very long service’. With 48 employees by 1881 and 110 by 1888, housing for new workers was a priority for the Fox family. However, there were too few Fox cottages, and the first major private housing development started in 1887, with the sale of the 166 acre Glentrammon Estate opposite the Oak Brewery. New residential roads were formed and by 1896 over 100 cottages had been constructed.

Fox-built Cottages

The Fox cottages, many surviving

today, were drained, like the adjacent 1851 Fox-built school, ‘by

cesspit and glazed pipes.’ Sanitation, property size, ventilation and

heating, and a garden for the cultivation of fruits and vegetables were

increasingly important for tenants. Barnard observed in 1888 that

‘Messrs. Fox and Sons do all they can for the comfort and happiness of

their men’ and ‘there are thirty cottages on the property, each with a

plot of garden ground for the employee’. The average weekly rental for

two and three bedroom cottages, with almost eight years remaining on the

lease, was 4 shillings in 1884. This compared favourably with weekly

rents in three employer-provided model housing developments: Saltaire,

built between 1850 and 1875, between 2s 4d and 7s 6d; Bournville,

constructed between 1893 and 1912, for smaller cottages without

bathroom, 5 shillings; and Port Sunlight, built between 1888 and 1914,

for smaller houses, 6 shillings.31 However, the amenities supplied by

Salt, Cadbury and Lever were more extensive than the Fox facilities.

The Fox cottages housed all workers in 1871, while housing for the enlarged workforce of the 1880s was provided by the private house-building programme started in 1887. Thus, cottages provided for Oak Brewery workers were constructed to the latest standards of comfort, convenience and sanitation, next to their workplace and at fair rents.

For the brewers, good housing provision ensured longevity and continuity of employment, while paternalistic scrutiny of workforce activity could be maintained.

Recreational facilities for employees and local community

In 1836, the public house provided most working-class leisure. The pub was said to provide ‘a recreational nexus’ and ‘an all-purpose service institution in working-class life’ providing a meeting place for societies, gambling, dominoes and cards, reading matter, food and drink. Insobriety and uncivilised behaviour concerned the middle-classes, so also did meetings involving the ‘potential insurrectionary plotting’ of Luddites and Chartists. Drunkenness caused much hardship, particularly in poor households.Middle-class concerns about working-class leisure activities made them, ‘keen to ensure that the proletariat was spending its free time in an uplifting fashion…away from their taverns and beershops’.

Four alternative types of working-class leisure came to the fore. Firstly, the state controlled supply, largely through licensing, and later supplied directly with such amenities as parks, sports facilities and libraries; secondly, leisure was provided by the working-classes themselves; thirdly, voluntary bodies and philanthropists provided leisure; lastly, commercial leisure, like fairs, theatre and the circus, was available.

The hope of weaning people away from bad habits by the provision of counter-attractions came to the fore in the 1830s. Initially, providers concentrated on intellectual pursuits, but from mid-century increasingly added physical activity. The middle-classes wanted to attract people away from ‘uncivilised pursuits’ such as excessive alcohol consumption, cock-fighting, prize-fighting, swearing and brawling among themselves, and crime. Also, those from different classes could fraternise and come to understand each other.

These middle-class ambitions for ‘conversion’ applied mainly to men. Although some women drank in public houses and many participated in family leisure outside the home, after marriage ‘the husband and wife move for the most part in separate spheres’: female leisure, particularly if women worked only at home, consisted of ‘essentially a female network of support based on the separation of male and female worlds after marriage’.

The state provided no leisure in the area in 1836. There was self-provision of leisure, in pubs and elsewhere. Although owners of three public houses in Green Street Green, Fox leisure provision came under the ‘voluntary and philanthropic’ heading, taking many forms.

Entertainment was often provided by travelling fairs and circuses, involving members of the large Gypsy community, some living permanently on Farnborough Commons, and others wintering there before travelling through Kent to work in agriculture. Farnborough was chosen for its osier beds, providing twigs to make baskets, pegs and skewers, for customers in populous areas towards London. Farnborough Gypsy Horse Fairs attracted buyers and sellers from throughout Kent. Horses were galloped along the High Street, watched by local people, who also enjoyed the stalls and entertainments offered.

Visiting fairs were held: at Green Street Green every May, with ‘sports, games, sideshows, curiosities and agricultural trading’; at Keston with Pettigrove’s swings and steam-driven roundabouts; at St. Mary Cray, where a Michaelmas Statutory Fair had been held annually for centuries; and two circuses in Farnborough, Diddle’s, in a tent holding thirty people, seats costing three pence, and Fossett’s.

T.H. and Walter Fox, soon to become Magistrate and senior member of the Special Constabulary respectively, were involved with Gypsy encampments on Farnborough Commons. In 1887 the brothers, Sir John Lubbock and local businessmen formed a Committee of Farnborough Commons Conservators, proposing to enclose them to prevent ‘debris left by a succession of Gypsy encampments’. By June 1888, a Bill permitting enclosure had passed through Parliament, and in April 1889 the Commons were cleared and entrances ‘banked up’. The Commons retained their original legal use, but ‘encroachment’ was prohibited. Conservators may however have been said to spend much of their time enforcing petty restrictions which they did not apply to themselves. For example, the Fox brothers laid waste pipes and constructed a road on the Common adjacent to the brewery.

The hub of Fox family recreational facilities was the Brewery Clubroom, founded in the early 1880s, initially for brewery employees and their families, but by 1902 called the ‘Green Street Green Village Club’, ‘open to anyone above the age of sixteen years, subject to the approval of the Committee’. The Committee’s President was T.H. Fox, Vice-Presidents Walter Fox, Sir John Lubbock, and MP for Sevenoaks, county cricketer and MCC President H.W. Forster, the Committee consisting of ten local businessmen. Like its management, the Club Rules had a paternalistic middle-class ring. Rule seven stated ‘no betting or gambling shall on any account be permitted, nor shall any intoxicating liquor be sold, consumed, or brought upon the premises’. Rule twelve stated ‘any person using bad language shall be fined one penny for each offence’.

The 1905 Annual Concert held in the Clubroom was introduced by the Rector of Farnborough on a stage decorated with flags and pot plants, before a very large audience. Apart from six comic songs, the concert had a distinctly classical feel, with contralto, violin duets with piano accompaniment, soprano and tenor, all talented local performers. Details were recorded of the 1900 Annual Concert, again successful, despite poor weather. Proceeds were in aid of the local branch of the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Families’ Association, in keeping with the many charitable fund-raising activities of the Fox family. Among Clubroom activities were billiards, draughts, dominoes, whist and cribbage. In 1906 the Club team travelled by brake to compete against West Wickham, and in 1908 a team participated in the Bromley Quoits League.

The major Oak Brewery outdoor sport was cricket. T.H. Fox had captained the Tonbridge School Cricket XI in 1870. The family established the Oak Club pitch next to the brewery. T.H. and Walter Fox and other brewery employees made up the team, which played in a local league. Chelsfield Parish Magazines reported matches against Chelsfield and Goddington Cricket Clubs. The integrity of the Oak Club was praised: ‘We do not know of a single country club in this neighbourhood that confines itself to bona fide members. The only team even approaching this ideal is the Oak at Green Street Green’. Katherine, daughter of W.B. Fox, is mentioned frequently for her support of the Chelsfield Cricket Club, particularly for organising fundraising entertainments.

In 1905, the Green Street Green Rifle Club was founded, and a miniature rifle range installed at the brewery. The silver Fox Challenge Cup, given by Walter Fox and medals by T.H. Fox, were awarded annually to winning competitors.

Reading Rooms provided an alternative to the public house to counter intemperance, and were also bound up with contemporary attitudes to philanthropy, recreation and self-help and originally imposed upon the working-classes by the upper-classes, mainly the church and local landowners.

Farnborough Village Hall started life as the Parochial Reading Room, affiliated to St. Giles’ Church. In 1893, local dignitaries, including T.H. and Walter Fox, Sir John Lubbock M.P., his son John and Reverend Kelly, appointed themselves Trustees of a parish room to be built on village land purchased for fifty pounds.

No membership or activity details at Farnborough exist as few early Trustee meetings were recorded. However, the Indenture of 4 December 1895 detailed many proposed uses for the room, including library, recreation and entertainment, technical classes, Friendly Society meetings, Sunday school, several religious functions, gymnasium and drill hall, choir practice, Band of Hope meetings, Mothers’ Union, Girls’ Friendly Society, Lads’ Brigade, football and cricket clubs, societies ‘promoting religious, philanthropic, charitable or benevolent purposes’, and collecting for ‘penny banks, dispensaries and clothing clubs’. In the twentieth-century, with increasing numbers of alternative distractions, reading rooms were deemed old-fashioned and many, including that at Farnborough were renamed ‘village halls’.

Despite T.H. Fox’s position as Treasurer of the National League for the Prevention of Destitution, the Fox brothers were responsible for frequent imprudent borrowings secured against brewery assets between 1884 and 1909, making few repayments, which resulted in the bankruptcy and closure of the brewery on 15 July 1909, with around 110 redundancies. This had many consequences, including the departure from the area of many former employees, six of whom played for the Green Street Green Football Club. The Club was threatened with closure unless new players could be found. However, at the Village Club’s annual general meeting, the Fox brothers offered its continued use by the local community, under the same rules and Committee control. Much later it became a Working Men’s Club, affiliated to the Club and Institute Union (C.I.U.), closing only recently.

The alcohol ban was unpopular and dominated debates during the 1866-7 C.I.U. conferences. The temperance nature of the clubs deterred working men from becoming members. Rules were reluctantly changed to allow beer consumption if food was provided, but excessive drinking resulted in expulsion. Working men, resenting middle-class ownership and interference in club administration, resolved to repay patrons’ loans. By 1884 loans were repaid, clubs became self-governing and were, for the first time, managed by working men for working men, enabling them to raise such matters as Union and political subjects with impunity.

Thus, not only was Fox family provision of recreational activity appreciated by their employees, but also helped to ensure that the temptations of excessive alcohol consumption in public houses, mostly Brewery-owned, were curbed.

Conclusion

Fox family workers’ housing was built: out of necessity, to attract employees to the area; in the interests of retaining staff, whose houses ‘went with the job’; to paternalistically provide comfortable accommodation with modern facilities at fair rents close to the brewery; and within sight of directors’, head brewer’s and brewery clerk’s residences, where workers’ behaviour could be observed.While recreational facilities helped attract Oak Brewery workers away from the evils of alcohol, including from their own public houses, and created a disciplined context in which they could be managed and ‘improved’, they undoubtedly derived enjoyment from the sports, games and entertainments offered.

Provision of working-class women’s facilities was sadly neglected, consisting mainly of Sarah Fox’s Mothers’ Union activities. This neglect emphasises that the main anxiety of the brewery Foxes was their male workers’ behaviour, as only two of their 48 workers in 1881 were women.

Culture, sport and entertainment were offered in typically Victorian paternalistic fashion: to control the behaviour of the working-classes at leisure; to improve the ability of the owners to retain staff; to offer what were considered attractive alternatives to alcohol and the public house; and, in altruistic fashion, to make workers’ lives more enjoyable.

THE LOCAL AREA

Workers' Housing elsewhere

In 1842 Edwin Chadwick, commenting on a Report from the Poor Law Commissioners, concluded that ‘whilst an unhealthy and vicious population is an expensive and dangerous one, all improvements in the condition of the population have their compensation’. He cited one employer who, after making costly improvements to workers’ housing and providing a school, ‘was surprised by a pecuniary gain’.On 4 January 1841 the Chairman of the Bedford Union wrote to the local Assistant Poor Law Commissioner, detailing improvements in workers’ behaviour after moving into new cottages provided by employers: they ‘feel raised in society’; the husband is ‘stimulated to industry’; having acquired advantages, ‘he is anxious to retain and improve them’; he ‘becomes a member of benefit, medical and clothing societies’; he sends his children to a Sunday school and, where possible, a day-school; and the family attends church regularly.

In similar vein, the Mines Inspector Hugh Tremenheere referred to ‘men of the worst moral character, or of turbulent and disaffected dispositions’, then wrote of workers’ housing built at the Cwm Avon Works in South Wales in 1846, where cottages were ‘well arranged’, ‘substantial and roomy’, and had ‘neatly kept gardens’, ‘a public oven and all other proper conveniences’ and ‘proper covered drains’. Also, two hundred larger cottages with four rooms and ‘a small court behind’ were under construction. He mentioned ‘windows of ample size’, and had seen papered rooms, excellent furniture and books.

Thus, to improve the moral character and propriety of behaviour of the working-classes, government officials applauded the paternalistic provision of workers’ housing by employers in the 1840s.

However, as commented about Saltaire, Titus Salt’s industrial settlement in countryside near Bradford between 1850 and 1875, housing for employees was not built entirely for philanthropic reasons: ‘Motives, as always, were mixed. The first houses….were built for employees who otherwise would not be available’. Salt’s other motivation for building his mill and Saltaire, with fine quality workers’ accommodation and community facilities, was his dismay at the appalling condition of working-class dwellings in Bradford. As a magistrate and Mayor of Bradford, he was shocked at ‘what seemed like the casual immorality of working-class town dwellers’. With authority over his tenants in Saltaire, he created a sense of order, discipline and improvement, in paternalistic fashion.

Welfare schemes were introduced, largely to cope with labour difficulties in the nineteenth-century. These included medical facilities, pensions, profit-sharing, sports and social amenities, churches and chapels. There was also company housing, in the well-known cases of employers like Rowntree, Cadbury, Salt, Lever, Guinness, Reckitt and Colman and, perhaps for rather less philanthropic motives, in the gas, iron, railway, chemical and brewing industries.

Workers’ housing was built by railway companies to address the need for accomodation in rural areas including the London and Birmingham Railway Company in Wolverton in 1848, the Great Northern Railway by the 1860s, and the North Eastern Railway who had built 4,606 cottages by 1902.

The Coalbrookdale Iron Company purchased Pool Hill Estate to provide cottages in 1838.

By the 1860s, seven factory villages had been established around Middlesborough by ironmasters, as were many in South Wales. The South Metropolitan Gas Light and Coke Company constructed workers’ cottages around London in the 1870s. Brunner, Mond, a chemicals company, was established by Unitarian John Brunner and partner Ludwig Mond in 1873 in Cheshire. Workers’ cottages were built in Northwich, and sick pay, medical facilities, a social club, sports ground, school, library and accident insurance were established.

Brewery Companies

Brewing, consisting mainly of family firms, practised paternalism widely until 1900. With small-scale production, brewery owners and managers came to know employees personally, and welfare schemes were important in establishing good employer-employee relations. Companies provided housing to create settled communities in which ‘work-discipline was easier to maintain’ and ‘gratuities commonly won the deference employers needed for the exercise of authority over their workers’.By 1889, workers’ cottages had been built by Samuel Allsopp in Burton upon Trent, Charrington’s in Mile End and Watney’s in Pimlico, where approximately 650 employees were housed.

Edward Greene took over his father’s brewery in Bury St. Edmunds in 1836, the year John Fox founded his Brewery. With similar rates of growth (Greene had 21 employees in 1851 and 90 by the early 1880s), both breweries were managed paternalistically. Greene offered higher wages than local Suffolk farms and treated employees benevolently. Many remained there all their working lives. Greene also provided workers’ housing, purchasing and building properties from 1859, until by 1887, more than forty, housing over half his workforce, were owned. This paternalism resulted in ‘a devoted workforce and a low turnover and reputation as a good employer’.

Westgate Brewery House and Oak House, the homes of Edward Greene and John Fox respectively, were located prominently within each brewery complex, from which a paternalistic eye could be kept on day-to-day workplace activities.

However this was not universal practise.

George Gale of Gale’s Brewery, Horndean in Hampshire, did not practise paternalism, providing neither housing for employees, nor enjoying the ‘traditional loyalties known to exist in brewing’ including longevity of employment. He lived in Southsea, some ten miles from his brewery, meaning that no close or paternalistic relationship was developed with his men’.