THE FOX FAMILY AND RELIGION

This article has been developed from Chapter 2: Involvement in Religion. of

'Michael Frederick Kempton U8737912 A826 - a dissertation submitted for an MA degree in History in 2014'.

It is reproduced here with the permission of the author.

Introduction

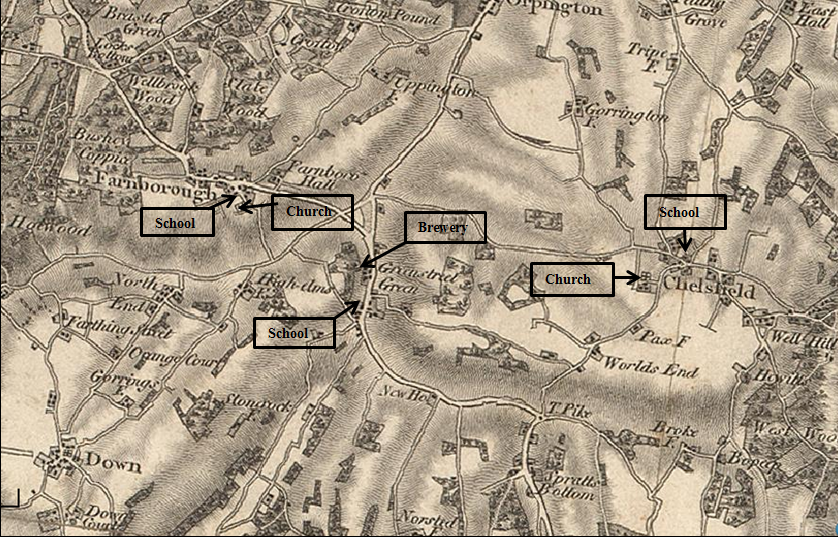

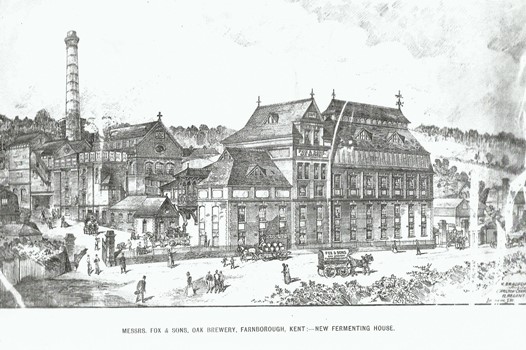

This article concerns the local provision of religious facilities by the Fox family, and the impact of their beliefs on philanthropic activities. Their strategy, in establishing a settled community almost from scratch, free from social disorder, to enhance their standing within it, to redress the balance between competing Protestant denominations and to instil their moral values into both workforce and community, is investigated.Anglicanism, Methodism and Congregationalism, the Christian denominations of three generations of the family, in Green Street Green, Farnborough and Chelsfield, are explored.

Location of the Brewery

Access from Green Street Green to both Farnborough and Chelsfield parish churches required the negotiation of steep paths, difficult in winter

After their father’s death, J.W. and T.S. Fox realised that a facility for Anglican worship in Green Street Green was desirable, particularly as a small congregation of Baptists, including Ebenezer Morrison, the brewery’s Head Brewer for 31 years, started meeting around 1870 in the cottage of another brewery employee William Crafter.

Baptists held similar beliefs to Congregationalists, except that for the former, children were baptised only when they could understand its meaning.

Permission was granted in 1872 for occasional Anglican services to be held in the Schoolroom. Visitation Returns were submitted approximately every four years by the clergyman to his Diocesan Archbishop (Canterbury for Farnborough and Chelsfield), detailing the interaction between church, landowners, schoolteachers, farmers and workers, how this affected community relationships and church-going, and the level of Dissent. Clergymen felt that church was central to parish communal life and that harmony depended upon their being able to conduct their work without hindrance.

T.H. and Walter Fox obtained permission from the Farnborough Rector to hold Sunday evening services regularly in the Brewery Clubroom from 1893. When in 1903 the installation of a billiard table precluded this arrangement, evening services reverted to the Schoolroom. Chelsfield Parish Magazines frequently recorded thanks to the Fox family for facilitating these services, usually conducted by Reverend Welch of the Bromley Union (the workhouse was in Farnborough parish). In his 1880 Visitation Return, the Farnborough Rector George Hingston stated that parish Dissent was strongest in Green Street Green.

In 1875 T.S. and J.W. Fox had tried to reduce this strength, particularly among brewery employees, where Dissent may have led to trade unionism and possible industrial unrest. On hearing of Ebenezer Morrison’s intention to purchase land for a Baptist Chapel, they attempted to buy it themselves, only to discover that ‘Mr. Morrison had anticipated them by twelve hours’. Morrison, who conducted the services, erected an iron Chapel in 1882, later replaced in brick

Anglicanism thrived in small parishes with arable agriculture and a strong dependency system of landowning squire and church minister, where workers and tenants were expected to follow landlords to church, reducing the possibility of Dissent. In Green Street Green however, few workers followed their brewing, land-owning landlords to church. Despite the family’s efforts, Anglicanism remained weak there, services taking place in the Clubroom only in winter and only ‘fairly well’ attended. Although disadvantages suffered by non-Anglicans, like the inability to hold public office, were removed by the early 1830s, others remained, causing conflict between Nonconformists, and Anglicans and the state.

Handicaps concerning church rates were not resolved until 1868, access to ancient universities until 1871 and burial rights until 1880. Neither discrimination against Dissenters nor a strong dependency system in Chelsfield prevented William Beardsworth Fox from advancing the cause of Nonconformists.

W.B. Fox rented from Chelsfield Lord of the Manor William Waring, the 135 acre Lilly’s Farm in 1853. Even after inheriting approximately £4,000 from his father in 1861, W.B. Fox continued as a tenant farmer, leasing two further farms from Waring, making a total of over 1,000 acres in Chelsfield, largely of cereals, fruit and hops.

Methodists had been in Chelsfield since the early nineteenth-century, but it was recognised as a Centre only in 1840, in 1843 appearing on the Sevenoaks plan, or ‘circuit’, with visiting preachers.

Most of W.B. Fox’s agricultural workers were Dissenters. The replacement of inadequate facilities for Methodist worship in Cross Hall, a cottage shared by Wesleyans and Bible Christians, to counter the Anglicans’ strength, was important to him.

The Cray newspaper announced the laying of a foundation stone for a new Chelsfield Wesleyan Chapel. There followed a meeting of 120 persons in a meadow lent by W.B. Fox ‘whose name will live long in the memory of Chelsfield friends, and whose heart is ever willing to help the good work. Within twenty weeks, the Annual Missionary Meeting of Chelsfield Wesleyans was held in the new chapel with W.B. Fox as chairman. He stated that ‘a churchman’ had given £10 towards the building fund and that ‘he hoped that the day was not far distant when he should see the Vicar in the chair’, a surprising wish, indicating that the latter was sympathetic to Methodism, with congregations of ‘for the most part farm labourers’.

The relationship between Chelsfield’s most prominent Methodist W.B. Fox, tenant farmer from 1853-1896, and Folliott Baugh, Rector of Chelsfield from 1849-1888 was extremely cordial. In 1868, Baugh married Anne, daughter of Fox’s landlord Waring, who in 1872 gave half an acre to extend St. Martin’s churchyard, over which Fox had waived his rights, to allow this. Fox also contributed towards the cost of a new parish church heating system and had a reputation for always subscribing to good causes in the parish.

With commendable frankness Baugh, answering a Visitation question concerning impediments to his ministry in 1864, responded: A thousand acres have been for some years occupied by a zealous dissenter who employs dissenters by preference. The agricultural poor dissent from social causes, they have the worst seats in the church, and see the best occupied by farmers, whom they do not love. They prefer to worship among themselves. They prefer too, extempore preaching, declamatory and familiar, which they seldom get at church. The only remedies I can suggest are a Clergy trained to preach extempore and recruited from a lower class. The zealous Dissenter was W.B. Fox. In 1876, Baugh went further, stating that Dissent had been increasing in Chelsfield and neighbouring parishes for 25 years, and ‘the agricultural labourer will prefer any kind of dissenting place of worship to that of the established church which he associates with authority and oppression’.

Partially blaming his father-in-law for letting farms to ‘a proselytizing dissenter of large success’ he proceeded ‘very many who used to attend church irregularly, went off to the chapel. I am bound to say that the Wesleyans who regularly attend their chapel services are some of the best respected people in the parish’. In the 1864 Farnborough Return, Baugh stated that elementary education was provided only by two private schools (managed by Sir John Lubbock, T.S. and J.W. Fox), and that education would be improved by ‘a good National School in which the clergyman could have some influence over the young, which now is impossible’. Chelsfield had had a National School for some years funded largely by Waring and Baugh. Thus Anglicans Waring and Baugh shared an unusually cordial relationship with Nonconformist W.B. Fox, who farmed much land in Chelsfield, demonstrating a positive feeling of tolerance and cooperation within the village community.

W.B. Fox had also displayed beneficence towards his chapel and its congregation, as well as philanthropy in his many local public duties, including Chelsfield School Board member, Way Warden, Guardian, Overseer and Board member of the St. Mary Cray Fire Brigade. He died on 20 March 1896. Later in life he had changed his religious allegiance, his obituary stating that ‘he was a prominent member of the Congregational Church of St. Mary Cray, and much respected throughout the district.’ His sons Edwin and William also worshiped there.

Employers liked to set an example to workers by attending church regularly. Working-class attendance distracted them from potential social disorder in the public house, and from politics and trade union activity. The working-classes derived greatest comfort from church in difficult times, but were often deterred from attending through lack of good clothes and inability to pay pew rents, if any. However, this appeared not to be the case in 1893 at St. Giles Farnborough, when Reverend Kelly reported that his 217 ‘unappropriated sittings’ were free, the average congregation numbered 200 and most of the population was ‘poor’, indicating that the congregation included a fair proportion of working-class parishioners.

To the credit of the Fox and Lubbock families, deeply involved at St. Giles for many years, it does not seem that ‘to most working-class people the churches were alien, middle-class institutions where people felt out of place’.

The Religious Census of 1851 revealed that church or chapel attendance was usually identified with the middle, far more than the working-classes. For the former, attendance was a social requirement, regardless of religious belief. Family church-going was part of respectability in the mid-nineteenth-century. Church patronage emphasised the social standing of members of the gentry.

Farnborough churchyard contains many Fox family graves; the current lych gate was donated by the family in 1902; and the interior of the church incorporates several family memorials, including a stained glass window above the altar commemorating T.S. Fox. The most exalted component of Fox patronage however, was an organ, donated in 1887 by T.H. Fox, churchwarden and organist for many years, after exchanges concerning its location, between him, Reverend Kelly, the Archbishop of Canterbury’s architect and even the Archbishop himself.

A cheaper way of encouraging further patronage was to publish subscription lists, the most generous at the top and the least at the foot, illustrated by lists, including Katherine Fox, daughter of W.B. Fox, in Chelsfield Parish Magazines. Interestingly, Katherine did not follow her father or brothers into Nonconformity, but became a generous patron of St. Martin’s Church and Chelsfield Cricket Club. She also shared a house in Chelsfield for 33 years with Congregationalist brother William.

.

Women were generally considered more religious than men: in terms of ‘separate spheres’, the middle-class family home was supervised by a woman whose moral influence counteracted the world’s temptations and the ‘evils of commerce’ encountered by her husband. The few activities permissible for middle-class women outside the home included voluntary and philanthropic works.

Several Fox family women were involved in schools as voluntary part-time teachers, supervisors, visitors and prize-givers, in which fathers, husbands and brothers were managers or Board members. Mothers’ meetings, working parties, Clothing Clubs, Shoe Clubs, parish nurse, Sick and Poor Fund and support for a local Charity Hospital, were all causes associated with St. Martin’s..

The Mothers’ Union, including the Green Street Green meeting led by Sarah Fox, had many members, largely from the working-classes, early in the twentieth-century. Its aims included making clothing for the poor, training mothers in childcare, cooking, religion, needlework, contributing female companionship and arranging outings and teas. In 1901, Sarah Fox addressed the Chelsfield mothers’ meeting, reminding members about ‘the children God had given them’ and ‘how much depends on the mother as to their conduct in life’. In the Brewery Clubroom in 1895, their meeting was provided with a tea, recitations and music, and in 1902, Sarah Fox again addressed the Chelsfield meeting, the Rector tendering his thanks for ‘her able and helpful address.’

In 1904, the Chelsfield Working Party, including Sarah’s niece Katherine, made red flannel jackets for Cray Charity Cottage Hospital patients ‘who, through illness, have gone there to be carefully tended and nursed’. .

In summary, even though Fox family faith had emphasised their local status, relationships with staff and members of their community, regardless of denomination, were cordial, and religion had influenced their philanthropic activity.

Conclusion

Until a small Anglican church was built in 1905, temporary facilities for worship in Green Street Green were provided by the Fox family in the Schoolroom and Clubroom which they founded as part of community-building undertakings. Despite this provision, both philanthropic and to counterbalance the rise of Dissent which they felt was detrimental to their business, Anglicanism in the hamlet failed to thrive until after 1905.The family worshipped at Farnborough parish church for generations, bestowing patronage in spiritual and material ways, as well as enhancing their social capital with other land-owning friends, and setting community members an example. Public distrust of business was assuaged through religious faith, family integrity and business owners’ philanthropy, all demonstrated by the Fox family. Mothers’ meetings, Sunday schools and Working Parties, were all philanthropic activities stemming from their faith.

Anglican sermons, renowned for encouraging the working-classes to accept their station in life, did not seem to deter them from attending services at Farnborough, the brewing family church. At St. Martin’s however, working-class congregation members were lost to the Methodist chapel, where aspiration was encouraged.

Before moving to Chelsfield, W.B. Fox had been an Anglican. He then became a Methodist tenant farmer, employing Dissenters. He co-founded a new Chelsfield Methodist chapel, before later becoming a Congregationalist. He participated in much philanthropic activity and contributed greatly to the community’s harmony, maintaining excellent relations with the Rector, who was equally well-disposed towards Nonconformists, despite the exodus from his church. Religious harmony existed also within W.B. Fox’s family, sons William and Edwin joining their father in Congregationalism but daughter Katherine, who shared a house with William junior for many years, worshipping at St. Martin’s Church.

Considering the relatively modest scale of their businesses, the extent of religious philanthropy demonstrated by the Fox family was significant among employers, at least equal to that of Edward Greene, although rather less perhaps than the wealthier major philanthropic Nonconformists discussed in the article at the side.

THE LOCAL AREA

Religious Context

The Church of England had experienced internal dissent leading to the foundation of new Protestant denominations within ‘Old Dissent’ in the seventeenth century, and ‘New Dissent’ after the eighteenth century Evangelical Revival. The latter arose after clergymen underwent intense conversion experiences involving the forgiveness of sins and salvation of souls. Inequality of clerical stipends also caused discontent.Anglican congregations too were dissatisfied with absent clergy, those administering several parishes and with other careers, and endured dull sermons. Some Anglicans remained within the established church as Evangelicals, while others followed John Wesley, who founded Methodism. Characterised by members’ exuberance, confidence, enthusiastic hymn-singing and discussions of spiritual progress, Methodism eventually comprised several branches. By 1836, while the Church of England remained the established or ‘state’ church with power and influence in Parliament and among landowners, Methodism was becoming increasingly popular, particularly with artisans, shopkeepers, the farming community and, particularly women, who were denied many active duties within Anglicanism. Methodist membership approached 300,000 at this time, with many more non-members attending chapel.

Congregationalists, previously Independents were, like Baptists, Unitarians and Quakers, part of ‘Old Dissent’. The Congregationalist Union, founded in the early 1830s, was self-governing, independent, without bishops or presbyteries and its followers believed in predetermined salvation, Christ dying only for the elect

The national census of religion in 1851 indicated that approximately 7.7% of the population were Methodists, 4.4% Congregationalists, 8% other Nonconformist denominations, 5% Catholics, 25% Anglicans and the remainder, about half, did not worship regularly.

The relative isolation of the factory village was used as a basis for putting a variety of philanthropic theories into practice’. This paternalism, a development into village life of the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century household, including family, servants and apprentices, was adopted by John Fox, a middle-class farmer, exemplifying ‘the close proximity of the employer and his employees to each other in small industrial village communities’.

Religion and Business

Respectability was extremely important in an environment of low business morality and considerable insecurity in the nineteenth-century, commercial success depending upon a reputation for ethical behaviour. Linking a business with an institution unrelated to the world of commerce and renowned for its strong principles, would certainly have enhanced its reputation.The Church fulfilled such a requirement - religious institutions and business were closely identified in the nineteenth-century. Apart from religion, the only other widespread upright institution functioning outside the commercial marketplace, was the family, with values of ‘loyalty, trust and altruism.

Brewers were usually Anglicans and Conservative Party supporters, rather than Nonconformists and Liberals, who often favoured temperance. The former included Edward Greene of Greene King, of strong faith and ‘insistent that his Christian principles were the basis of his business life’. He believed in hard work, business integrity and fair treatment for his workers. Congregationalists, Liberals and paternalists, Titus Salt and William Lever built model villages including workers’ housing, churches, schools and recreational facilities at Saltaire and Port Sunlight, respectively. Both were tolerant of other religions. Intolerant of alcohol, but under pressure from tenants, they reluctantly permitted its sale in off licences. Liberal and Baptist Jeremiah James Colman became a Congregationalist in his forties and believed in total honesty and straightforwardness in business and his personal life. He too built houses for his workers and was responsible for much philanthropy. Liberal Jesse Boot made several Nonconformist allegiances, but also enjoyed Anglican services. Although he and wife Florence promoted the welfare of employees, Boot’s greatest philanthropic venture was in retirement, when he funded a college in Nottingham eventually becoming Nottingham University.

There were similarities in linking business with religion and family, both seen as possessing ideals of solidity and integrity, between the Fox family and the five major industrialists, with Greene the closest in terms of magnitude, politics and religion.

Thus, Fox family men were committed Anglicans, and in the case of W.B. Fox and his sons, Nonconformists, enabling them to demonstrate through church and chapel attendance and philanthropy, their respectability and integrity, essential for business. Fox family women involved themselves in middle-class philanthropic activities, such as charitable fund-raising, education and religion.

Sunday Schools

Before compulsory education, many children did not attend school, but worked providing essential income for poor households. Sunday schools provided the only training in reading and sometimes writing for many of these working-class children, probably including those in Green Street Green before the elementary school opened in 1851.Farnborough and Chelsfield had schools by 1836. Concern for social order among the young on Sundays encouraged the middle-classes to support schools as ‘key agencies in the inculcation of orderliness, punctuality, sobriety, cleanliness and related virtues governing personal behaviour and social discipline’, also important attributes among workers.

In 1851 in 23,135 Sunday schools in England and Wales, about 2.6 million children (approximately 75% of those between five and fifteen) were instructed by 250,000 teachers, and ‘the schools taught more children to read and write than any other educational institution’. All denominations sought to recruit future congregations from their Sunday schools, of which 45% were Anglican. Towards 1900, Nonconformists had difficulty in converting adults to their faiths, instead concentrating on Sunday school pupils. .

The Farnborough School Board consented in 1886 to a Sunday school in the Green Street Green Schoolroom between 9am and noon. Accounts of treats and prize-giving at the ‘Chelsfield Sunday schools’, comprising Green Street Green, Chelsfield and Pratt’s Bottom, were recorded. In February 1899, Sarah Fox, involved in local education since 1851, handed prizes to Green Street Green Sunday school pupils with high marks for attendance and good conduct. In February 1900, the children were given tea, played games, sang songs and were entertained by T.H. Fox, who amused them by demonstrating his phonograph machine, to ‘hearty cheers at the conclusion’. In August 1903, 153 children from the Sunday schools attended a short service at St. Martin’s, marched behind a local brass band to Rectory Meadow, where they participated in races, followed by tea and cakes. Messrs. Fox were thanked for providing waggons to bring in children from the outlying hamlets and for sacks used in the sack races.